Dual Coding Theory has been gaining a lot of attention from teachers around the world over the last couple of years, but what exactly is it and how can teachers use it to help their students gain a deeper learning?

What is Dual Coding Theory? Allan Pavio discovered that our memory has two codes (or channels) that deal with visual and verbal stimuli. Whilst it stores them independently, they are linked (linking words to images). These linked memories make retrieval much easier. The word or image stimulates retrieval of the other.

When teachers employ a dual coding mindset to their learning materials, the student’s cognitive load is reduced and their working memory capacity is increased, thus, learning is improved.

Whats is Dual Coding Theory?

Back in 1971, Canadian researcher, Allan Paivio, formulated his dual coding theory. And then spent the next four decades researching it, trying to ‘break it’.

He didn’t manage it.

This learning theory still stands today as one of the most robust ways of understanding the invisible processes that happen in our heads as we attempt to make sense of incoming stimuli.

His most significant discovery was that we have two separate channels that deal with verbal and visual stimuli.

While being independent of each other, they are also able to create what Paivio called “associative connections” between them. So, they are both apart from one another but can cooperate in forming linked pairs of words and images.

By forming such a link, the encoding process is enriched.

It leaves a double memory trace and, in the words of Professor Paul Kirschner, results in “double-barrelled learning” because of the resultant double opportunity of being retrieved by either verbal or visual means.

Dual Coding and Cognitive Load

Encoding, of course, is psychologists’ term for learning and, so, such a powering up of the encoding and retrieval processes deserves teachers’ close attention.

It’s no surprise then that John Sweller — the originator of the related Cognitive Load Theory— concludes that:

“Working memory capacity can be effectively increased, and learning improved, by using a dual-mode presentation.”

(Cognitive Load Theory, 2011, Sweller, Ayres & Kalyuga)

Often, cognitive science brings bad news to students. They are confronted by the facts that learning happens through thinking hard (Coe), that the comforting habit of rereading and highlighting is very inefficient, and that studying one topic at a time is less than optimal.

Dual coding is quite different in that pairing words and images don’t incur any additional cognitive load and also greatly helps retrieval.

It’s a ‘freebie’!

But, as good as this news is, it’s only half the story.

When Paivio found that the two channels worked as separate systems, he also noted that they were also fundamentally different in structure.

Verbal information, you won’t be surprised to learn, is sequential in construction. Words are joined together in “concatenation” as philosopher, Bertrand Russell, described it when comparing the relative merits of text and diagrams in conveying meaning.

Why are Visual Aids Important in the Classroom?

Visual information was defined by Paivio as being synchronous, or simultaneous’ in structure.

These two synonymous terms were used to explain that with diagrams, several, if not all, the elements could be viewed in one go.

Words, by contrast, have to be processed one at a time.

While Paivio noted these important structural differences, he didn’t devote his research to exploring them much further.

Others did, I’m glad to say, and we will shortly meet them and learn what they discovered. But, for now, we’ll stay with Paivio’s studies of the associative links between the two modality systems.

As robust as his findings were over several decades, we ought not to forget that the nature of the content learned by his laboratory subjects was cognitively unchallenging.

Like Ebbinghaus in the century before him, Paivio used simple content in order to discount any element of comprehension messing up his pure work on retrieval.

That’s not how schools work though, they do deal with cognitively challenging content.

The knowledge organizer with its lists of facts —let’s acknowledge it—while a very useful document, hardly represents the apex of schools’ intellectual aspirations.

Instead, different approaches are needed to mesh together such isolated facts into coherent networks and integrated concepts.

The Visual Argument (Larkin and Simon).

That’s where Jill Larkin and Herbert Simon come into the picture.

In 1987, they wrote a paper that developed Paivio’s distinction of sequential and synchronous information structures.

By comparing the time, effort and accuracy involved in understanding concepts communicated in either verbal or visual format, they arrived at what is now called “The Visual Argument”.

In their study, well-constructed diagrams were judged to be more computationally efficient than text.

Behind this somewhat technical term, lies this reasoning.

Because of the sequential nature of verbal information, each word is addressed one at a time. That, of course, isn’t all that’s entailed. To make sense of each word, they need to relate to others.

Sometimes this is simply the ones directly preceding them. But others may well be further apart in a previous phrase or sentence. Such distances require cognitive effort in searching and connecting in order to make the necessary inferences to make sense of the text as a whole.

Diagrams don’t work that way!

Constituent parts of a diagram are all significant, unlike the words in a piece of text. In addition, these visual elements can be perceived in one go, and not serially.

This is why Paivio described visual information being synchronous or simultaneous in structure. And this is why psychologists argue (Clark & Lyons 2004) that diagrams can be largely understood by using our everyday perception.

Graphics for Learning

Gestalt psychology, for nearly a century, has shown us that we immediately understand that proximity of elements represent commonality, as indeed does inclusion within a border (think Euler and Venn diagrams).

Analogy: Things closer together are more related. People living in the same house are more likely to be related in some way than people in separate houses.

These natural capacities are at play in the reading of diagrams and require considerably less cognitive resources than in reading texts.

The two cognitive, or computational, tasks that are more efficient with diagrams are the reduced need to search for relevant items within sentences and, correspondingly, the easier use of inference because metacognition is able to take place.

Put simply…

Reading texts involves an almost constant traveling back and forth searching which parts relate to which. This, then, makes inferences so much more difficult, or effortful, to make.

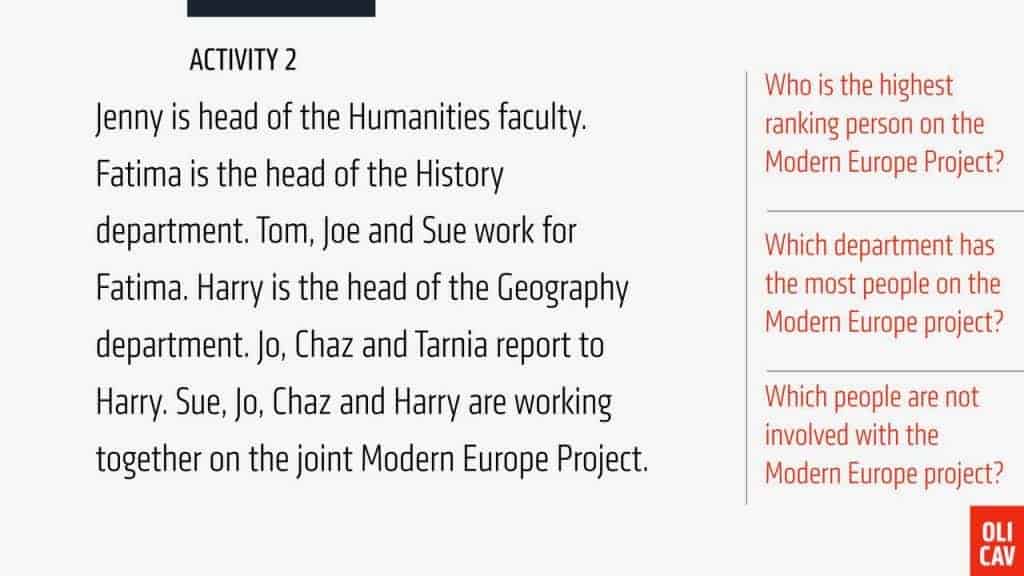

An Example of Dual Coding Theory

The example below, that I use in my presentations to make the concept of computational efficiency come alive, makes the point more effectively than my explanations.

From the text on the left, try and answer the questions. Difficult isn’t it!

Now try to answer the same questions by looking at the image below…

Much easier right?

Convinced of this you may be but, as always, there’s more to it than just presenting a diagram to your students.

As cognitive science authors, Clark and Lyons (2004) warn: “Visuals ignored, don’t teach”.

It’s all very well to give your students diagrams that convey information that require less effort to understand, but if you don’t then use them to make your students think, not much will be learned.

Diagrams should be thought of as platforms from which to better analyze texts and prepare for speaking and writing.

And then there are other problems to overcome.

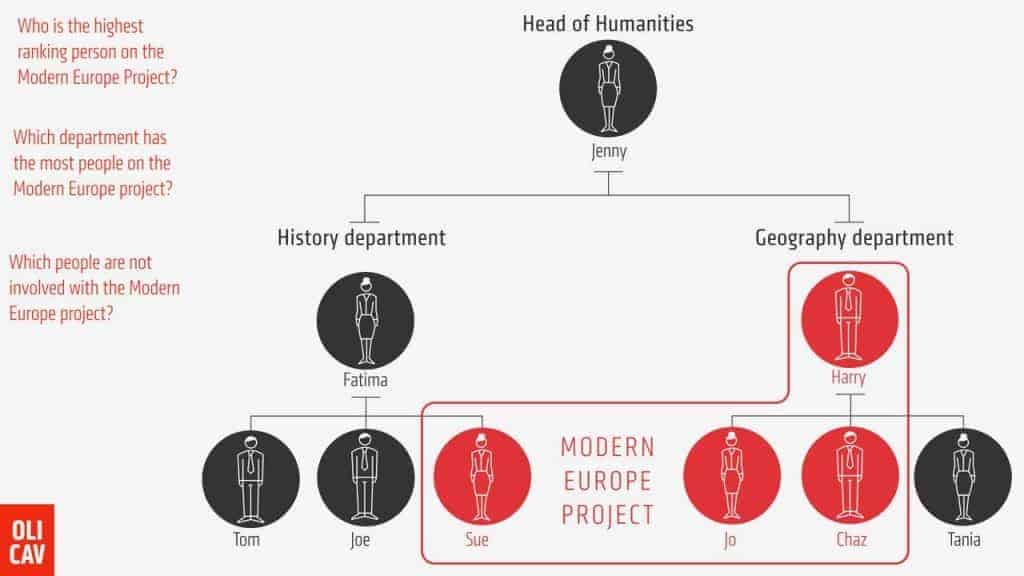

The Visual Argument only happens when teachers have chosen an appropriate visual tool. Exploring the differences between rural and urban settings is not best represented by a timeline for example. And plotting the plot of Hamlet becomes confusing if a mind map is used.

Deductive Reasoning in Dual Coding Theory

Graphic organizers can usefully be grouped along these four types of deductive reasoning:

- Defining

- Comparing

- Sequencing

- Linking cause and effect.

Identifying the nature of the knowledge task is essential before moving on to choose an appropriate visual tool.

As you might now expect, there’s one more danger to avoid.

Supposing the correct organizer is chosen to fit the nature of the task, its execution needs to be adequate.

Clark and Lyons (2004) highlight poor execution as a major factor behind dual coding’s diminished impact.

Above all, teachers need to make their handwriting legible. To be confident of this, printing in a clear, bold style with no flourishes or elaborations, is essential.

Forcing students to decipher a rushed handwritten script is an unnecessary cognitive burden that clearly bears an extraneous, unproductive load.

Other graphic considerations when creating dual coded communications involve the following four principles I devised after responding to requests for feedback from teachers on Twitter.

How to do Dual Coding

Firstly…

Simply to cut—reduce the volume presented on page or slide. It’s the easiest and most effective of all the principles.

Next…

Chunk the selected content. Identify the categories so it’s easier to make sense. And signal the chunks by providing more headings than you normally would.

Then..

Aligning the chunks, and any other element on the page —line or image— makes scanning and search so much easier for the reader.

In other words, don’t make them ‘artistic’ and random in placement. Order makes reading and scanning so very much easier.

Finally…

And lastly, continuing on the non-artistic perspective, practice restraint in the number and intensity of colors used, along with the use of a single typeface (font) ensuring it isn’t a fancy, hard-to-read display font or Comic Sans.

Typographers have a long history of theory, research and practice as to what makes reading easy.

Just look closely at any newspaper or magazine design and you will see these principles in action.

For a more detailed explanation of dual coding theory and examples of how it can be included in your classroom practice, Oliver’s book; “Dual Coding with Teachers” is perfect, it will be hugely useful to any teacher.

The diagram made things much easier. I my even make an assignment for the students to read that ( or any other type) of question, and make their own diagram. As long as you have problems that have a proper flow, I think this is a great way to visualize the problems and be creative in their own diagrams.

Interesting article. I agree with the article’s content and have always believed in the power of symbols. Key point is that teachers must be deliberate in the selection of their visual aids/diagrams.

When I introduce a new topic in social studies, I create easy to read and simple visuals to show the important info so students will focus on the over all idea rather than in all the detail.

When I introduce a new topic in social studies, I like to show my students different visuals to highlight the important information I aim to help my students focus on.

I understand how the use of images, visuals and organizers can help, but I am not sure how I could incorporate it into an elementary level music lesson. If I am comparing 2 songs, I may use a Venn diagram, but I am not using graphics regularly.