Let’s be honest: most parents want their children to participate in a school-gifted education program. It makes them feel good knowing their child is considered “gifted,” and most parents believe that being gifted places their kids on a path to success.

The truth, however, is more complicated. Although gifted education has distinct benefits, it has some potentially serious problems. Not every gifted child is happy, healthy, and guaranteed to be professionally successful.

In a previous article, we discussed the different forms of gifted programs offered in most K-12 schools. While many of the pros and cons depend on what type of program a school offers, we will consider more general aspects of gifted education in this article.

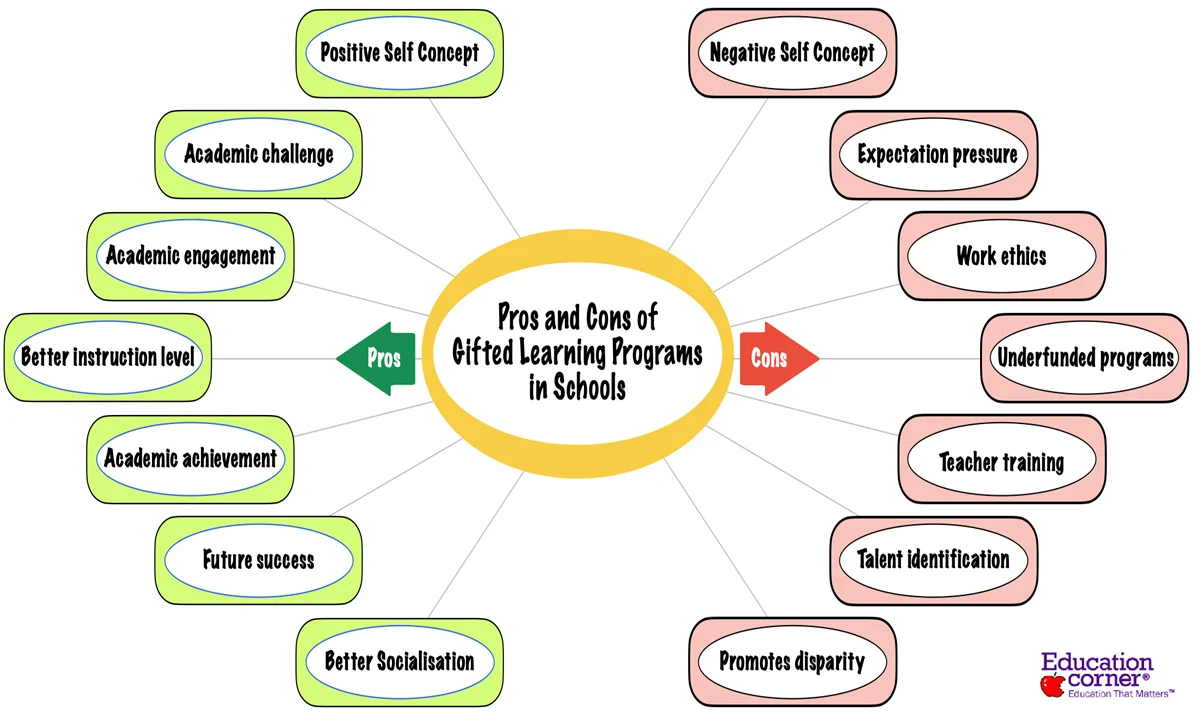

The Advantages of Gifted Education

Positive Self-Concept

Being labeled as gifted certainly boosts one’s self-esteem. Gifted students tend to achieve higher academically and feel better than non-identified peers.

Knowing that you are one of the “smart” kids can’t help but make you feel good about yourself. The effect is particularly amplified when the classroom is shared with non-identified students.

In literature, this is referred to as the Big-Fish-Little-Pond Effect, which means that it is better for academic self-concept to be a big fish in a little pond (gifted student in a regular classroom) than to be a small fish in a big pond (gifted student in the gifted classroom).

Academic Challenge

Gifted children often complain that their academic work is too easy and lacks challenge. This is because they learn differently from their peers and need additional challenges—outside the school’s standard curriculum—to stay happy and engaged.

Being in a gifted education program largely alleviates that concern.

Children are given work commensurate with their academic level and can progress at their own pace. In many gifted programs, students are placed with other gifted children who motivate each other to reach their fullest academic capabilities.

Kids are more likely to reach their potential when challenged academically.

Academic Engagement

Another frequent criticism of general education is that it is boring. Because kids are not challenged, they lose interest in their academic pursuits.

By increasing the difficulty of the work and focusing more on specific interests, students tend to stay more engaged in their education. Additionally, research has shown that creative interests first explored in gifted programs often remain intact into adulthood.

Raises Level of Instruction

Teachers are forced to raise their level of instruction when educating gifted students. This benefits not only the teachers who instruct but also non-gifted children in heterogeneous classrooms.

Many non-identified students can learn at elevated levels as a higher level of instruction pushes them to thrive, just as it challenges the gifted students in the classroom.

Student Achievement

Although this is a controversial subject (mainly because there is research to support both sides of the argument), evidence suggests that students in gifted programs exhibit higher levels of achievement than their peers.

In a meta-analysis of research over the past century, it was found that particular types of gifted programs—namely acceleration and ability grouping— had significant positive effects on academic achievement.

Future Success

There appears to be a link between students who obtain gifted education services and post-graduate academic success.

Several longitudinal studies have exhibited that children identified as gifted during grades K-12 go on to higher levels of graduate education, including a significantly higher percentage of doctoral degrees.

However, critics are also right to point out that many more highly successful people were not identified as gifted. Furthermore, numerous different variables affect future success.

Socialization

Gifted children often have different interests than non-identified peers. Being seen as different can lead to difficulties in socializing and a feeling that they don’t belong.

In a gifted program, students can find peers with similar intellectual pursuits, which helps them fit in better than in a general education classroom. This makes socializing more comfortable and finding friends easier.

In one study, students who were allowed early entrance to elementary school showed improvement in socialization and self-esteem compared to slight difficulties faced by advanced students who were not accelerated.

The Disadvantages of Gifted Education

Negative Self-Concept

If a gifted program separates gifted students from non-identified kids, then a gifted child may feel like a small fish in a big pond. This is the other side of the Big-Fish-Little-Pond Effect referred to earlier.

Research has shown that gifted students enrolled in special gifted classes will perceive their academic ability and chances for academic success less favorably than students in regular mixed-ability classes.

These negative self-perceptions can deflate students’ academic self-concept, elevate their levels of evaluative anxiety, and result in depressed school grades. A child might feel that he/she might not measure up.

A child may also struggle with low self-esteem, signs of which include negative self-talk, frequent mood swings, and an aversion to trying new things.

Expectations

Being in a gifted class creates more pressure on a student due to the high expectations of parents, teachers, and peers compared to regular classes.

For example, parents may push children too hard if they think they are gifted. Additionally, parents expect gifted children to be able to complete their work without much handholding and tend to become unsympathetic when a child struggles in a specific area.

It is important to remember that a gifted student may have varying strengths. For example, they may be gifted in math and science but not reading and writing.

When children are told they are gifted, they set high expectations for their abilities. This can lead to self-criticism when faced with challenges. Consequently, a child might stop trying due to fear of failure or may only attempt tasks they know can be completed without problems.

Lack of Work Ethic

Although this certainly does not apply to every child, when good grades and high praise are earned without much effort, a child may not learn the values and skills needed to be a productive, caring citizen who contributes positively to the world.

As children grow up, facing real-world challenges without an established positive work ethic can be difficult. Family and teachers must emphasize the importance of effort because breaking habits can be hard once they become ingrained in one’s behavior.

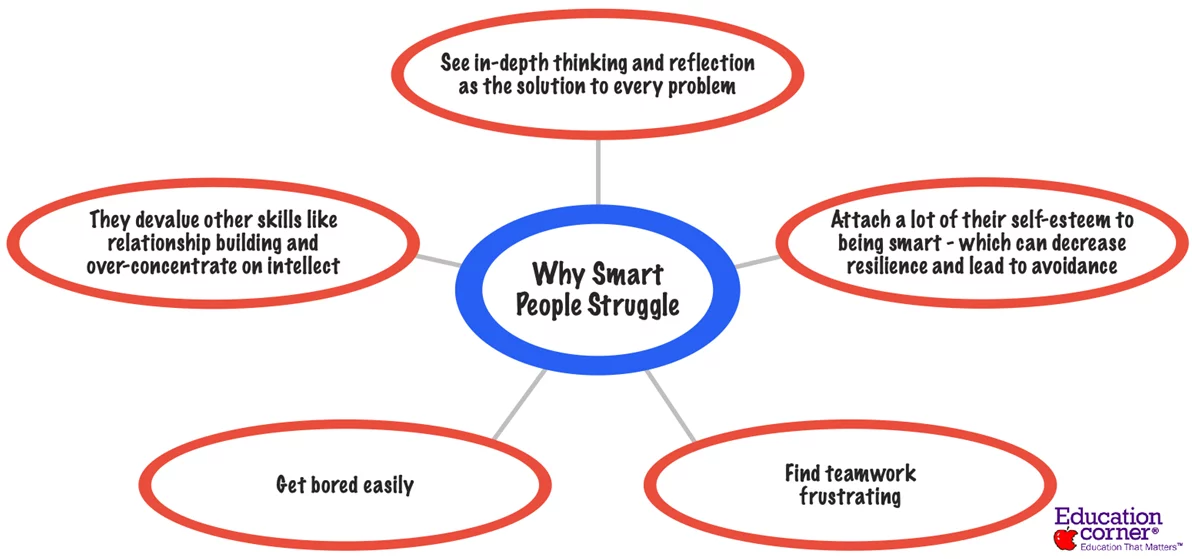

Raw intelligence is undoubtedly a huge asset, but it isn’t everything. Here are five things smart people tend to struggle with:

Dr. Anders Ericsson, a Florida State University professor, researched the relationship between IQ and attaining expertise in a specific area. He found that IQ may help initially grasp a skill, but there is no relationship between intelligence and excelling in an activity.

Effort and practice are crucial to achieving optimal performance. Therefore, students who do not develop a solid work ethic become disadvantaged despite their giftedness.

Gifted Programs Are Underfunded

How gifted education is funded varies greatly across countries. National and subnational education policy priorities, the structure of the education system, and the way in which educational resources are managed tend to impact the funding.

In most cases, gifted services are determined at the state and local levels. Because of the focus on general student proficiency marked by an emphasis on standardized achievement tests, not much money is allocated for gifted programs.

Gifted education is often an afterthought for many schools.

In the United States, for example, gifted education takes a backseat to prioritize policies such as “No Child Left Behind.”. A study from the Davidson Institute found that only 32 states provide some form of additional funding for gifted students, and only 4 provide enough funding to meet the needs of gifted students fully.

In the UK, educationalists believe government policies fail to recognize and support gifted and talented pupils.

A lack of funding at the national level particularly affects gifted, low-income kids who get left behind.

Teachers Are Not Adequately Trained

Teachers face problems on a daily basis when it comes to identifying gifted students and their classroom needs. No two gifted students are alike and can have unique needs. This means what works for one gifted student may not necessarily work for another.

Requirements for gifted teachers are generally established at a local level. Ideally, a gifted program should have special certification criteria for teachers, but this is not always the case. This potentially leads to a situation where gifted and talented programs are taught by teachers with no special expertise in teaching gifted students.

Additionally, a teacher without special certification may provide most of the instructions to students in gifted programs that use grouping and compacting strategies. A certified teacher may still take certain classes, but they are usually insignificant in duration compared to the overall instruction.

Identification of Gifted Students

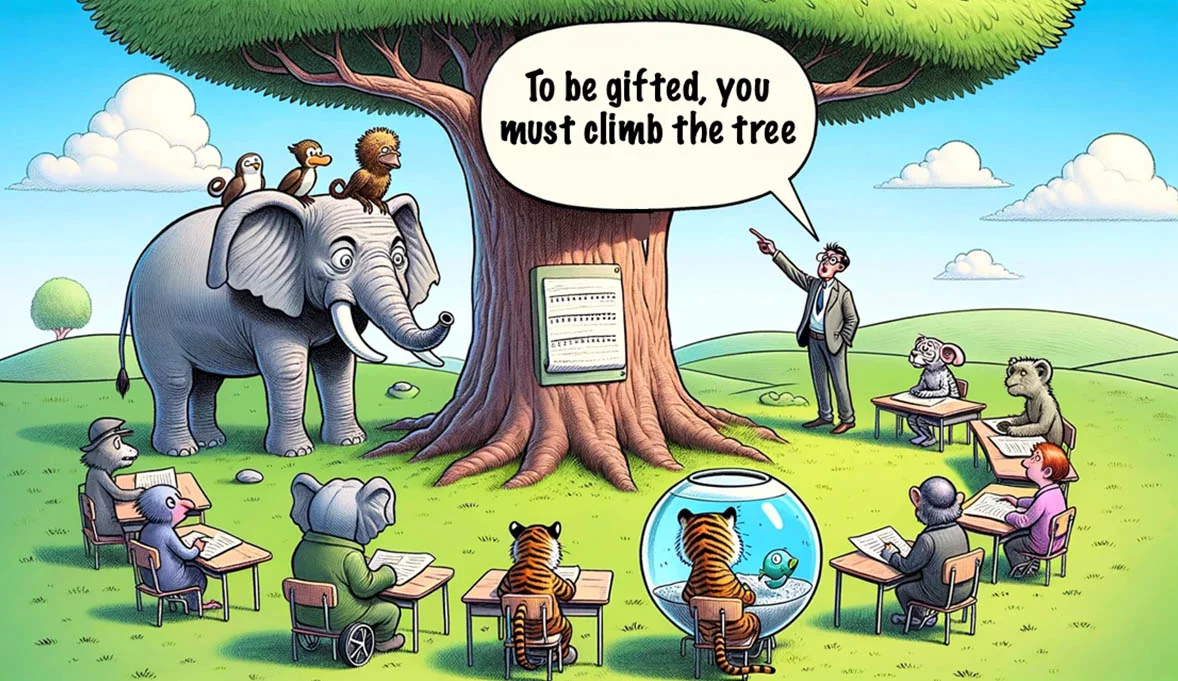

There is much debate in the field about how gifted children are identified.

Most of the time, an elementary school teacher initially identifies a child as having the potential to be gifted based primarily on their school performance. Once acknowledged as possibly gifted, the child undergoes some form of standardized testing.

This can be problematic for various reasons: First, general education teachers may not be adequately equipped to recognize gifted students (see more below); Second, a test score may not be a good indicator of giftedness.

Intelligence is a wide-ranging variable. Depending on the testing used, it may not encompass all facets of intelligence. The measures for defining giftedness are often narrow and can be manipulated by access to test-prep programs.

Moreover, many believe standardized intelligence tests favor the wealthy because they have had opportunities and experiences that poorer children do not.

Another issue with giftedness as a construct is that it is neither static nor dichotomic.

For instance, if testing occurs in the second grade, how can one say with certainty that the same student can still be considered gifted a few years later?

What about those who missed the cutoff by a point or two? They, too, might have been gifted but could have had a bad day during testing.

Once a child is labeled as gifted or non-gifted, it becomes difficult to change it later. And being gifted is never an all-or-nothing proposition. However, a standardized test based on cutoff looks at it that way and may not be a fair assessment of a student’s giftedness.

For these reasons, labeling children as gifted is fraught with problems. Some educators, such as James Borland, have called for the label of “gifted child” to be abolished.

Promotes Socioeconomic and Racial Disparity

The socioeconomic and racial disparity in gifted programs is probably the most controversial issue in gifted education. The National Association For Gifted Children notes that African American, Hispanic, and Native American children are underrepresented by at least 50% in gifted programs.

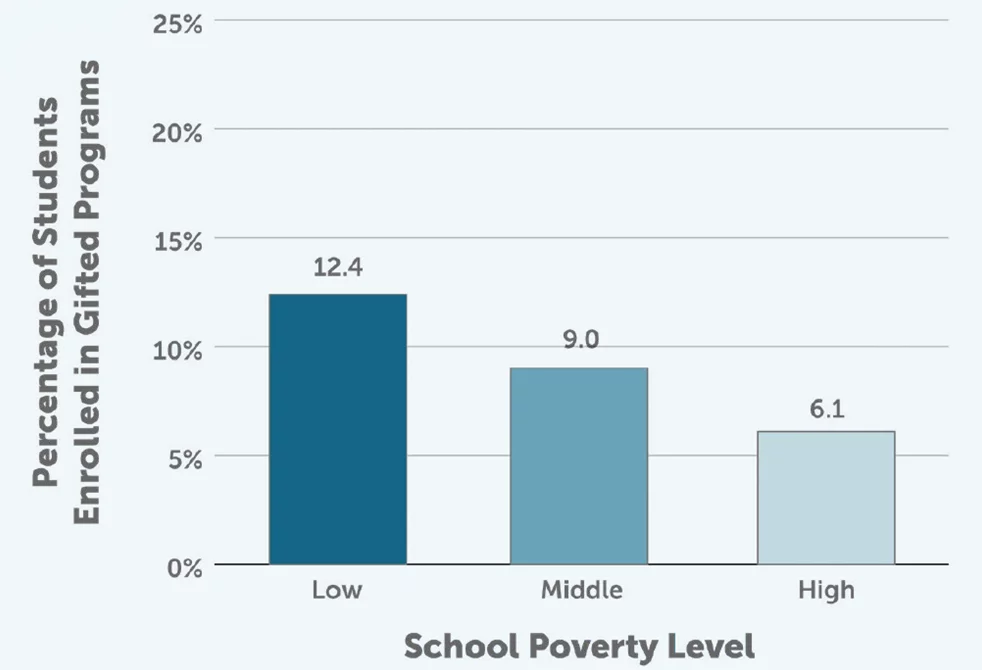

In a Fordham Institute study, researchers Christopher Yaluma and Adam Tyner found that 12.4% of students in wealthier schools participate in gifted programs, but that number is less than half (6.1%) in poor schools.

There are numerous possible reasons for these disparities. First, poorer schools, in most cases, need more resources to identify worthy students. Second, though they have as many gifted programs as wealthy schools, they often lack the means to identify gifted students accurately.

Screening students for gifted programs costs money. While wealthy parents, in most cases, push their children to be labeled as gifted, the same is not true with parents who come from poorer backgrounds.

Additionally, in minority communities, teachers may lack training in recognizing signs of giftedness, leading to misinterpretation of a child’s indicators. Parents, too, tend to be less informed about the process for identifying gifted students, resulting in fewer nominations.

For example, what is deemed precocious behavior in a white child may be seen as acting out behavior in a child belonging to a minority.

Teacher bias is a contentious topic in gifted education. Often, teachers do not realize they have these biases when they are asked to recommend students for gifted testing.

Sometimes, white teachers may have a conscious or unconscious bias against nominating minority children to gifted programs. A Vanderbilt University study found that high-scoring white students were twice as likely to be identified as gifted when compared to similar-scoring non-white students.

The same study also found that such bias disappeared when the teacher was non-white.

In fact, all else being equal, the same students were three times more likely to be assigned to gifted programs.

Racial profiling, whether intentional or not, is a real phenomenon that may be contributing to the inequity in gifted programs.

The Future of Gifted Education

Gifted Education has its proponents and its detractors. Although certain educators attack it, it does not appear to be disappearing anytime soon. There is a genuine need for programs in K-12 education that can help advanced learners thrive. Although being identified as gifted can lead to unrealistic expectations, it can also help students reach their potential.

Evidence suggests that gifted programs help students with academic achievement, socialization, and future success. Unfortunately, many gifted programs lack the necessary resources and are taught by teachers without the proper training.

Minority children and those of low socioeconomic backgrounds are underrepresented in gifted programs for a variety of reasons. It is imperative that qualified minorities and people of low socioeconomic status receive appropriate gifted services.

Fortunately, some of these issues can be addressed using technology. Remote learning, for example, can provide students with ready access to a full slate of advanced classes. Likewise, as use cases for artificial intelligence in education evolve, it could one day provide advanced content, personalized learning, creative writing, and critical thinking that match the learning needs of the gifted.

There’s much to be done. A broader approach to gifted education will ensure that more children reach their fullest potential.