There are an estimated 240 million children with disabilities worldwide. Inclusive education, as evidenced by research, is the most effective way to give all children a fair chance to attend school and learn and develop the skills they need to thrive.

According to the U.S. National Center for Education Statistics, over 95% of the students with disabilities were educated in general classrooms in the fall of 2022, and this share has been steadily rising. This means today, it is rare to have every student in a classroom competently working at the same grade level.

General education teachers can feel overwhelmed, undertrained, and unable to support students who work well below grade level and require additional support, not to mention a modified curriculum. When teachers lack the training and skills needed to teach students with disabilities, they can feel anxious and unprepared for inclusive environments.

A collaborative, team-based approach to educating students with disabilities, along with the knowledge of best educational practices for engaging all learners in core curriculum content, can help teachers overcome barriers and foster a productive learning environment.

This article discusses inclusive teaching dynamics that shape classroom experiences and impact learning. It also discusses strategies teachers can use to respond to these dynamics and be intentional about teaching in a way that empowers students.

A Brief History of Inclusive Education

Historically, public school education in the U.S. did not involve children with any kind of disability. People believed students with intellectual, physical, or developmental delays were better educated in separate settings, which often meant an institutionalized or residential placement where education was a low priority.

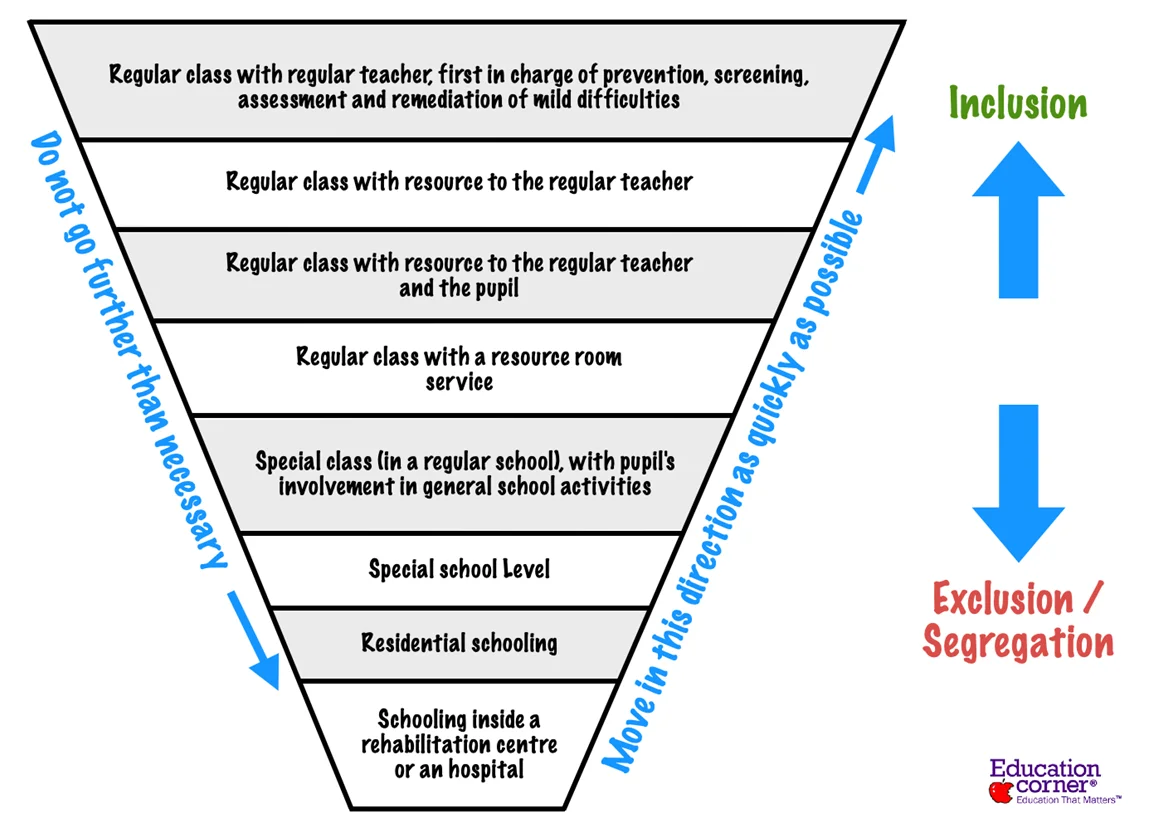

By the 1970s, schools began implementing a cascade model to guide the acceptance and placement of students with disabilities. Such placements included resource rooms and part-time and full-time special classes. A group of teachers were trained, and they, in turn, trained their colleagues on a particular skill or knowledge.

Eventually, the realization that students with disabilities have a right to the same education and experiences as their typically developing peers continued to gain momentum. The view that students with disabilities needed to “earn” their way into general education was seen as wrong.

In 1994, The Salamanca Statement on Inclusion in Education was adopted at the World Conference on Special Needs Education hosted by UNESCO and the Spanish Ministry of Education in Salamanca, Spain. The Statement and its accompanying framework catalyzed inclusive education worldwide.

In 2004, the U.S. adopted the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA), which made free appropriate public education available to eligible children with disabilities and ensured special education and related services. While IDEA does not use the word inclusion, it does state a preference for having students with disabilities placed in the “least restrictive environment.”

In 2015, the United Nations outlined 17 Global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), of which goal four focuses on education and strives to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.”

Defining Inclusive Education

The United Nation’s General Comment No. 4 (2016) on the right to inclusive education defines inclusive education as follows:

A process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures, and strategies in education to overcome barries with a vision serving to prodive all students of the relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience and the environment that best corresponds to their requirements and preferences.

These words can be misinterpreted in policy and practice without deep knowledge of inclusive education. It is thus important to stress the keywords and their meaning:

- Systemic reform means transforming the education system—no more ‘mainstream plus special.’ It means teaching all teachers to be teachers of students with disabilities, not just some. It means making the learning experiences and the environments in which children are expected to learn accessible to all.

- Overcome barriers is a direct reference to the social model of disability, in which disability is conceptualized as an outcome of the interaction between a person with an impairment and the social, political, and environmental barriers that impede their access and participation.

- Equitable means giving more to those who have less to equalize opportunity and redress disadvantage.

- Preferences and participatory refer to consultation, voice, and participation in decision-making and all aspects of schooling.

- Requirements stress the fact that students with disability have rights; they do not have ‘needs.’ The word ‘need’ positions people with disability as dependents, implying burden.

Mainstreaming, Integration, Inclusion: The Difference

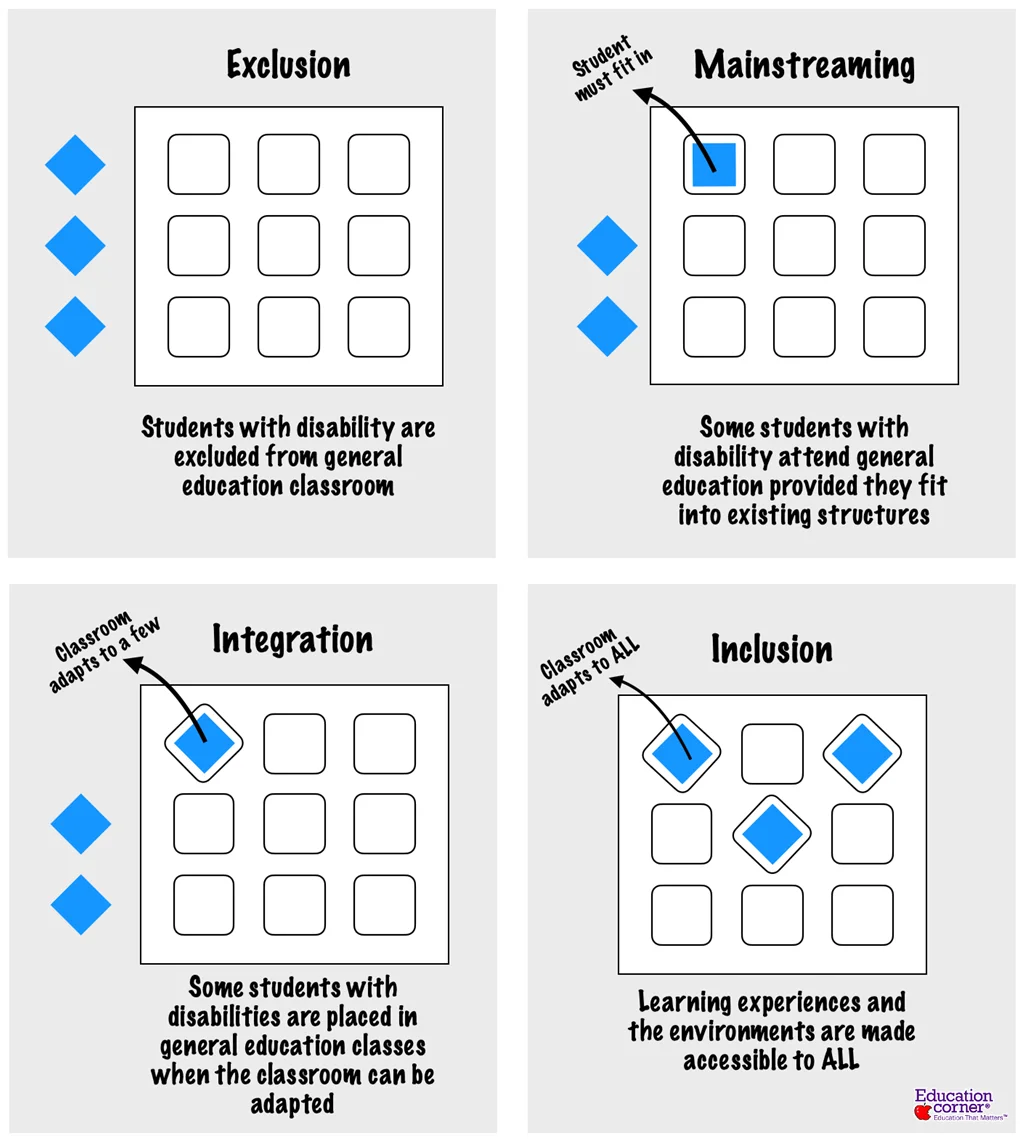

Inclusion can be easily confused with two other educational practices for bringing students with disabilities into general education classes: Mainstreaming and Integration. They are both significantly different from inclusion in their purpose and outcome.

(Image based on: Inclusion in Action by Nicole Eredics, Figure 1.3)

Mainstreaming gives students with disabilities access to the general education classroom, provided they can meet certain curriculum benchmarks. In essence, the student must fit into the existing classroom structures and systems.

For instance, if a student placed in a special education classroom can demonstrate age-appropriate behavior and grade-level skills, he or she may be eligible to spend part of the day in a general education classroom. The special education teacher still retains responsibility for the student’s overall education.

In integration, the students are one step closer to inclusion, but there are differences in their level of participation and sense of belonging. Students with disabilities are placed in general education classes only when the classroom can be adapted to meet some of the child’s needs.

For example, the classroom might need to be physically accessible or have the support of a paraprofessional. Depending on the child’s ability, the teacher may include the child in some lessons. If not, the child works on an alternative program with the paraprofessional, either in or out of the classroom.

A student under integration has more opportunities for peer interaction than a child who is mainstreamed. However, with the level of participation varying throughout the day, it can be challenging for the child to develop relationships.

Beliefs That Shape Inclusive Education

Inclusive education is based on the belief that:

- All students of all competency levels are welcome in general education classrooms.

- Every child is capable of learning. Rather than using medical labels or emphasizing a specific disability, inclusive educators teach all students based on their unique strengths and intellectual, social, emotional, and physical needs.

- The focus is on the individual child and his or her potential rather than differences or deficits.

- The need to “presume competence” in students with disabilities is upheld. When teachers presume competence, students with disabilities frequently engage in appropriate grade-level curriculum.

- Inclusive educators believe that the outcome of student-teacher interaction cannot be predicted. The best approach for teachers is to choose the most optimistic outlook possible and assume that students are competent in learning.

- Inclusive educators believe students must have the support, accommodations, and modifications they need to learn the same materials as the rest of the class. They value student differences and support their learning needs to the greatest extent possible.

Benefits Of Inclusive Education

Research consistently demonstrates numerous benefits to inclusive education. The following are some proven benefits for all students:

Emotional Benefits

Inclusive classrooms provide a sense of belonging by accepting students with various skill levels. They are responsive to student’s needs and focus on their strengths.

In 1954, renowned American psychologist Abraham Maslow developed the hierarchy of needs, which, in the context of education, means that students progress through a set of sequential needs from physiological to self-actualization. These needs must be met before the learning can begin.

Students with disabilities are particularly affected by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs because belonging, which is the third level of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, is something they are denied due to learning or physical disabilities that may set them apart from their peers.

Inclusive education also helps all students feel accepted and supported, meeting each child’s emotional and learning needs.

Social Benefits

As children go through their early life experiences, they form attitudes and beliefs about other groups, which may be harder to change as they grow older. They also develop prosocial skills such as empathy, impulse control, and self-calming skills, which are important for future success.

Students in socially inclusive schools have higher levels of respect for diversity, fostered by a high level of social interaction and the development of friendships between students with disabilities and their typical peers.

Students of all abilities also benefit from social interaction when they attend general education classes, eat lunch, and have shared experiences such as field trips and assemblies. They know one another by name and feel confident interacting with each other, all because they have had the opportunity to be together.

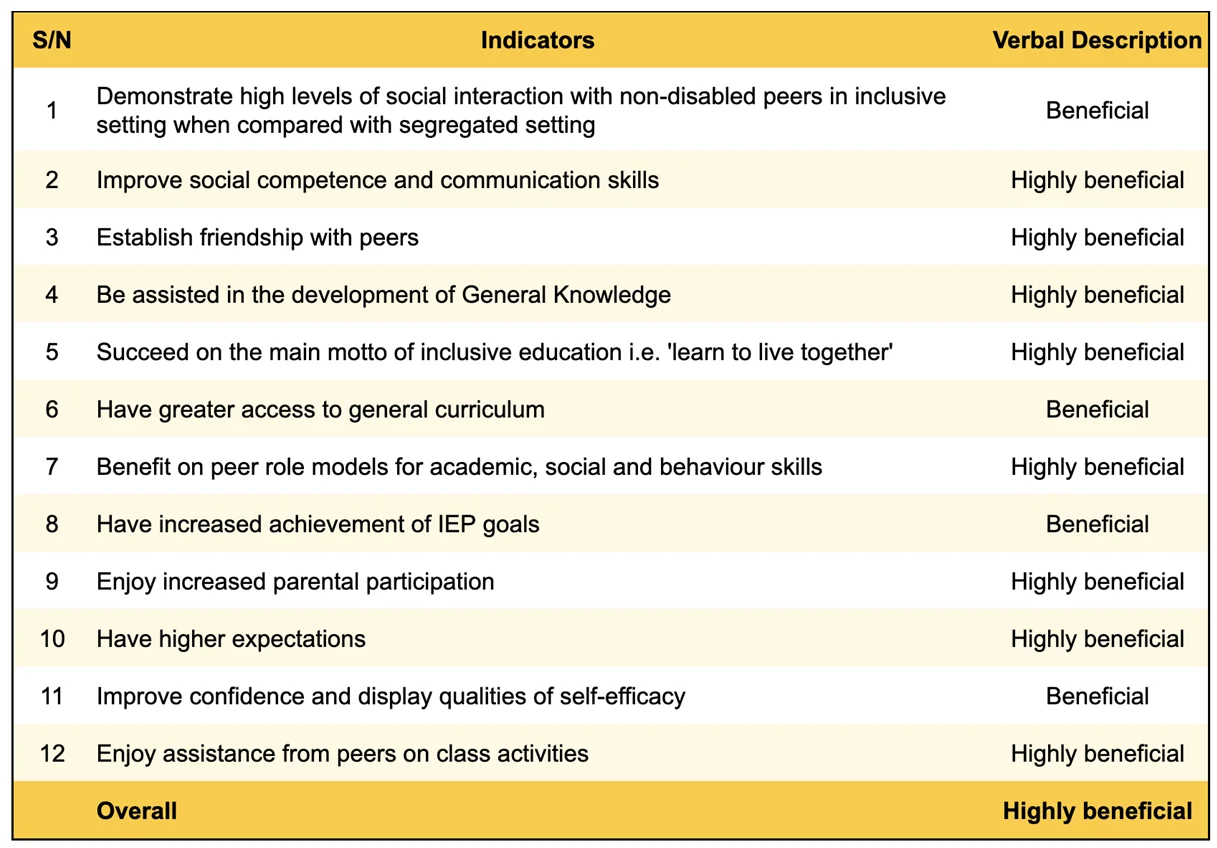

Benefits To Students With Disabilities

The table below shows teachers’ perceptions of the benefits of inclusive education on students with disabilities rated across various parameters. Overall, the research indicates that teachers perceive inclusive education as highly beneficial to learners with special needs.

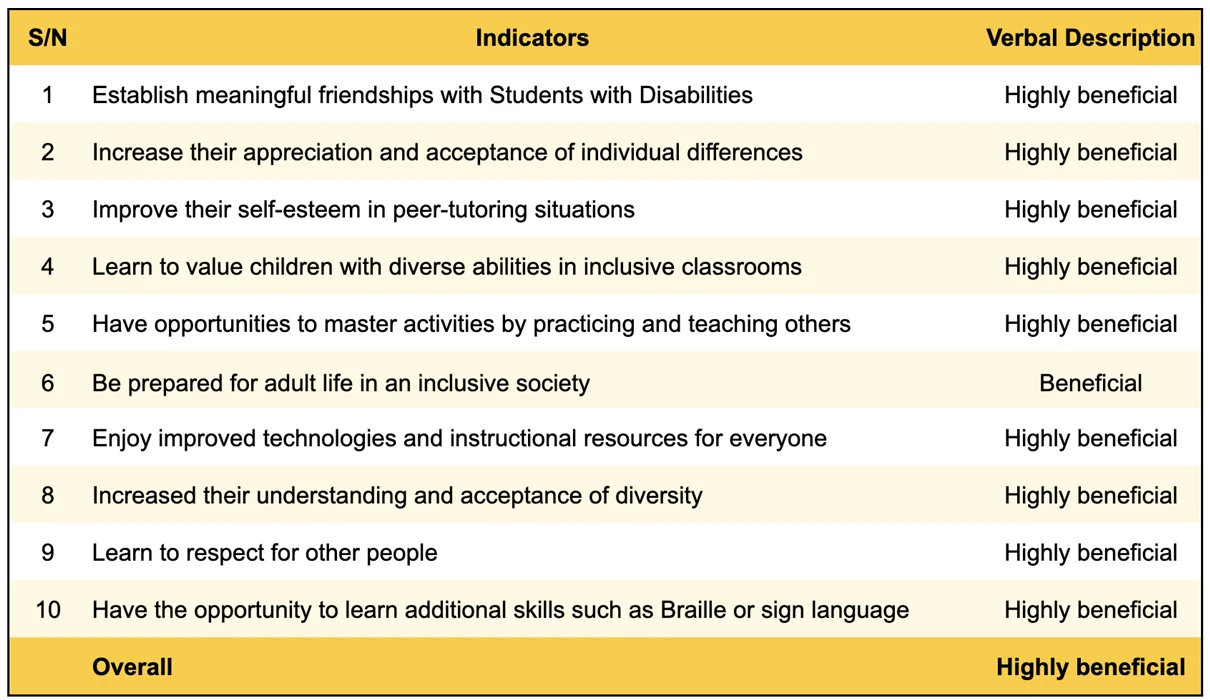

Benefits To Students Without Disabilities

Like the data above, teachers perceive inclusive education to be highly beneficial even to learners without special needs.

For learners without special, inclusive education helps build understanding and respectful attitudes toward diversity, learn about social abilities related to facilitating others’ learning, and enhance opportunities for academic learning and cognitive development by engaging in learning together and exchanging questions and knowledge.

Building Inclusive Classrooms

Successful inclusion in the classroom depends on the teacher’s collaboration with a range of professionals, including co-teachers and paraprofessionals. Input from family and community members who provide advice on meeting individual students’ needs is equally valuable.

Roles And Responsibilities

The classroom teacher

Inclusive teachers must see one another as members of the same team. They must share ideas, instructional strategies, and even classrooms. They must take primary responsibility for educating all students, including those with disabilities, model inclusive behavior, and set similar expectations for other class members.

The co-teacher

Co-teachers generally have less direct responsibility for shaping the general education curriculum but play a vital role in implementing curriculum with students whose educational needs differ from those of typically developing students.

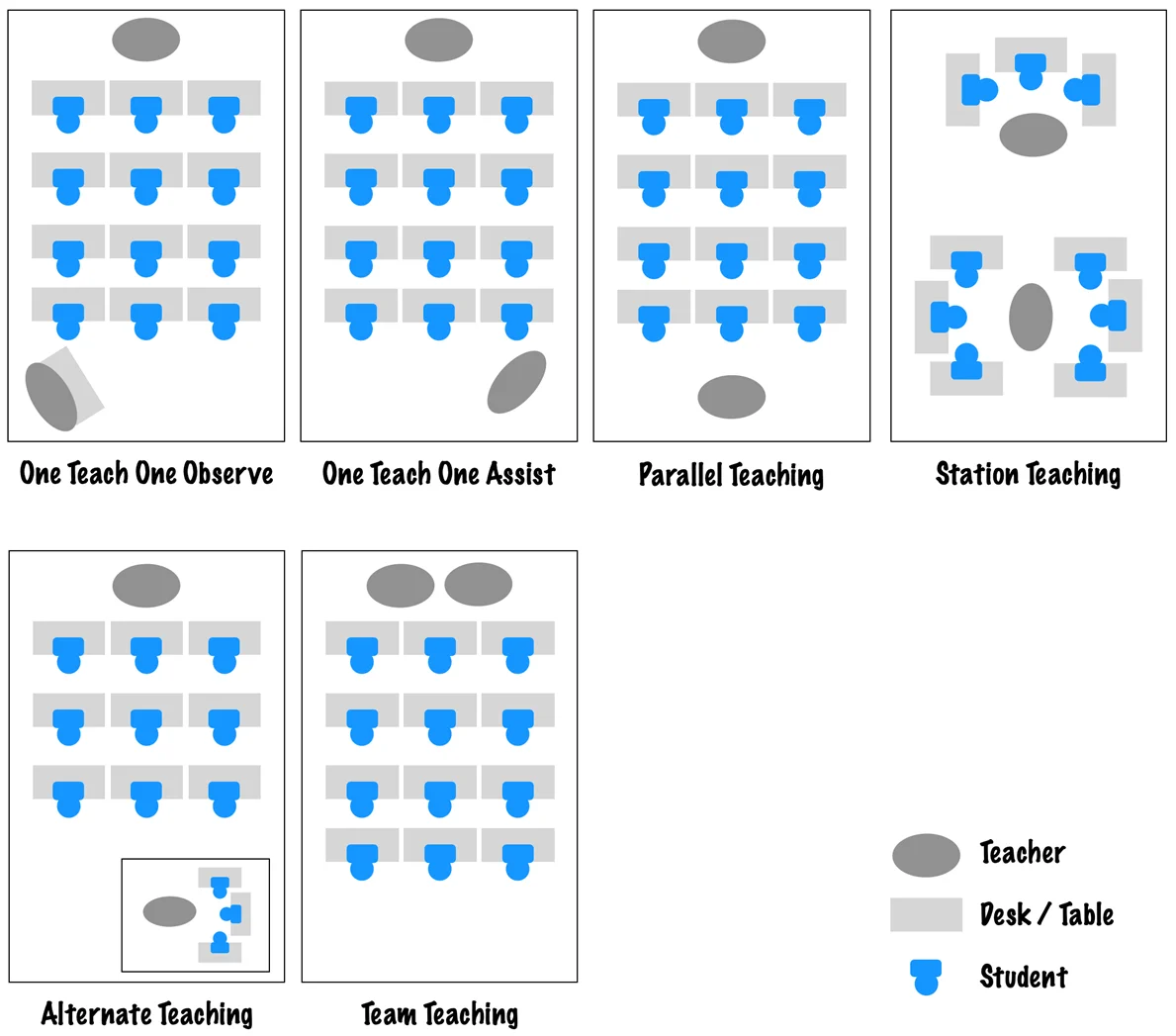

The type of support a co-teacher provides is typically intensive, specialized, and tailored to a student’s learning goals. It can be one-to-one or in a small-group setting for a period of time during the school day. Some of the co-teaching strategies are shown:

- One teach, one observe: one teacher teaches the class while the other teacher observes students and collects data.

- One teach, one assist: one teacher teaches the class while the other teacher walks around the class assisting students.

- Parallel teaching: one teacher teaches half the class while the other teaches the remaining students.

- Station teaching: one teacher instructs small groups of students for one portion of the lesson and then sends them on to the other teacher to learn the remaining material.

- Alternate teaching: one teacher leaves the room with a group of students to provide them with more explicit, direct instruction.

- Team teaching: both teachers share responsibility for delivering and planning instruction.

This paper, Co-Teaching: An Illustration of the Complexity of Collaboration in Special Education, covers more on co-teaching.

The Paraprofessional

A paraprofessional helps students access curricula and school life and assists during school hours with the students’ functional life skills. He/she does not replace the classroom teacher and is not responsible for determining educational programming and goals.

Depending on the state, district, or school, paraprofessionals are also known as paraeducators, para-pros, aides, teaching assistants, or independent assistants. In collaboration with the teacher and special education teacher, a paraprofessional helps students access the curriculum through accommodations and modifications to subject matter as necessary.

In an inclusive classroom, paraprofessionals are expected to fulfill several basic functions, including:

- Collaborating with members of the instructional team.

- Working under the direction of a teacher or specialized instructional support personnel such as occupational or speech therapists.

- Providing instructional and other supports designed by a licensed professional, such as giving physical assistance, helping with personal hygiene routines.

- Directing support and using modifications and adapted materials in a way that maximizes student independence, social relationships, and learning.

- Recording academic or behavioral data.

Families

Inclusive schools respect parents’ and guardians’ insight into their child’s abilities and needs. Such insights can significantly help a teacher plan appropriate educational support and activities. In addition, parents can be valuable resources by assisting with daily classroom activities and special events.

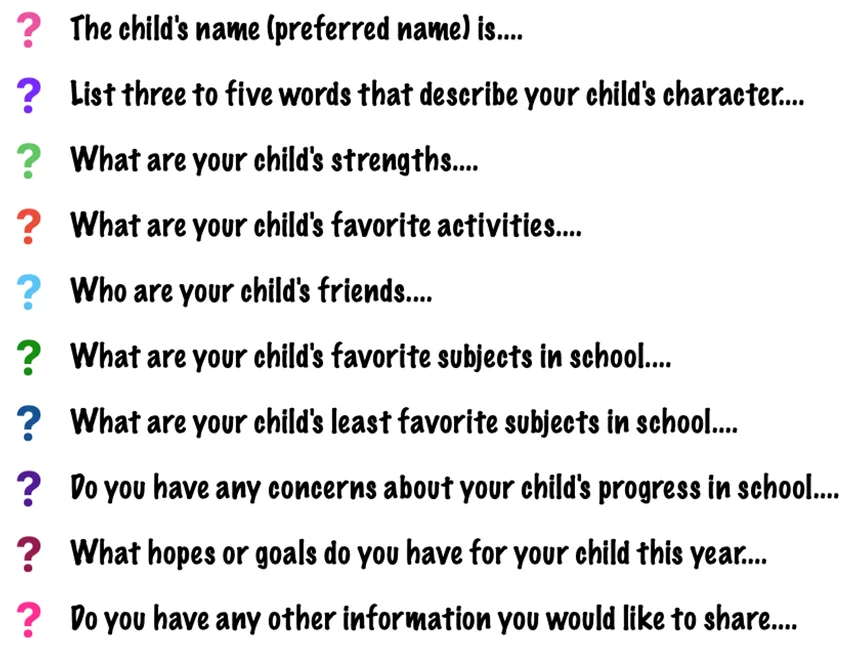

Sending forms or arranging private meetings with families (intake meetings) within the first two months of school helps teachers gather information about the student. Shown below are some example questions teachers can ask parents to know more about their students:

The tone of interest and respect opens the door to communication about the child’s development throughout the school year.

Strategies For Creating An Inclusive Classroom Culture

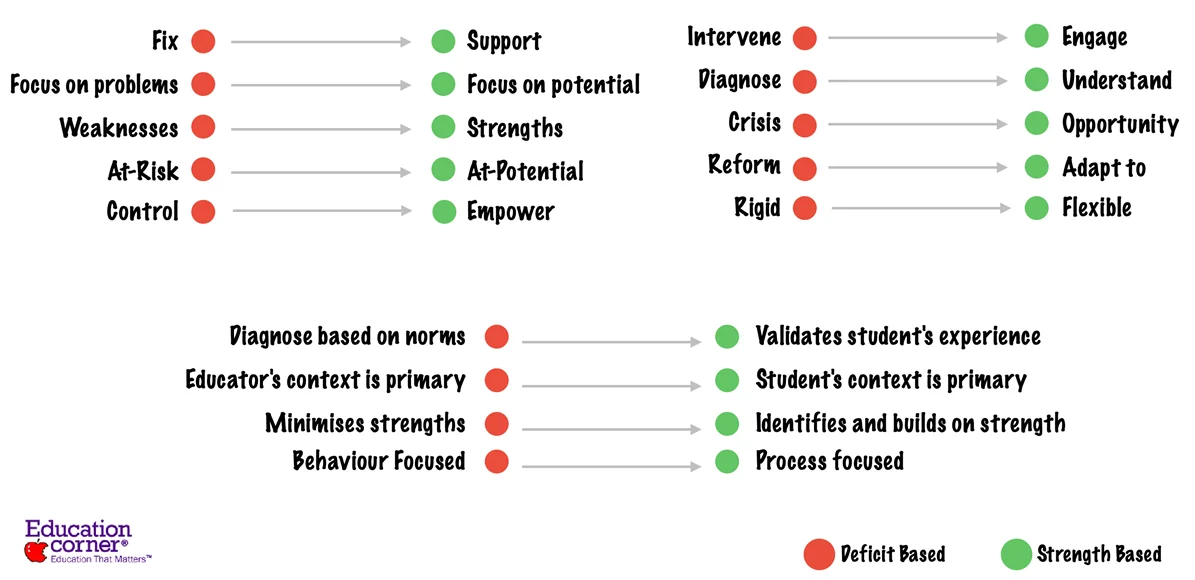

Establish a Strength-Based Classroom

In a strength-based classroom, there is a shift in thinking about student abilities. Rather than letting the child’s deficits or medical label define their potential as learners, a strength-based approach presumes competence.

It is based on the notion that if we ask people to look for deficits, they will usually find them, which will color their view of the situation. However, when we ask people to look for success, they will usually find it, which will also color their view of the situation.

As an educator, personalize learning experiences by practicing individualization. Think about and act upon each student’s strengths, encourage them to set goals based on them, and help them apply them in novel ways. Highlight unique student qualities and goals that make academic and social pursuits more successful and provide feedback on using those qualities to pursue meaningful goals.

Research has shown that networking with personal supporters of strengths development affirms the best in people. When educators are mindful of students’ strengths, they can help students to become empowered while strengthening the mentoring relationship.

Support Social-Emotional Development

Inclusive classrooms are also places of social-emotional development. The diversity of an inclusive environment provides a natural opportunity for social and emotional learning where students grow as human beings.

They learn to control emotions, empathize with others, set and achieve goals, have positive relationships, and maintain those positive relationships. Research shows that young children with well-developed social competence skills lead healthier, successful adult lives.

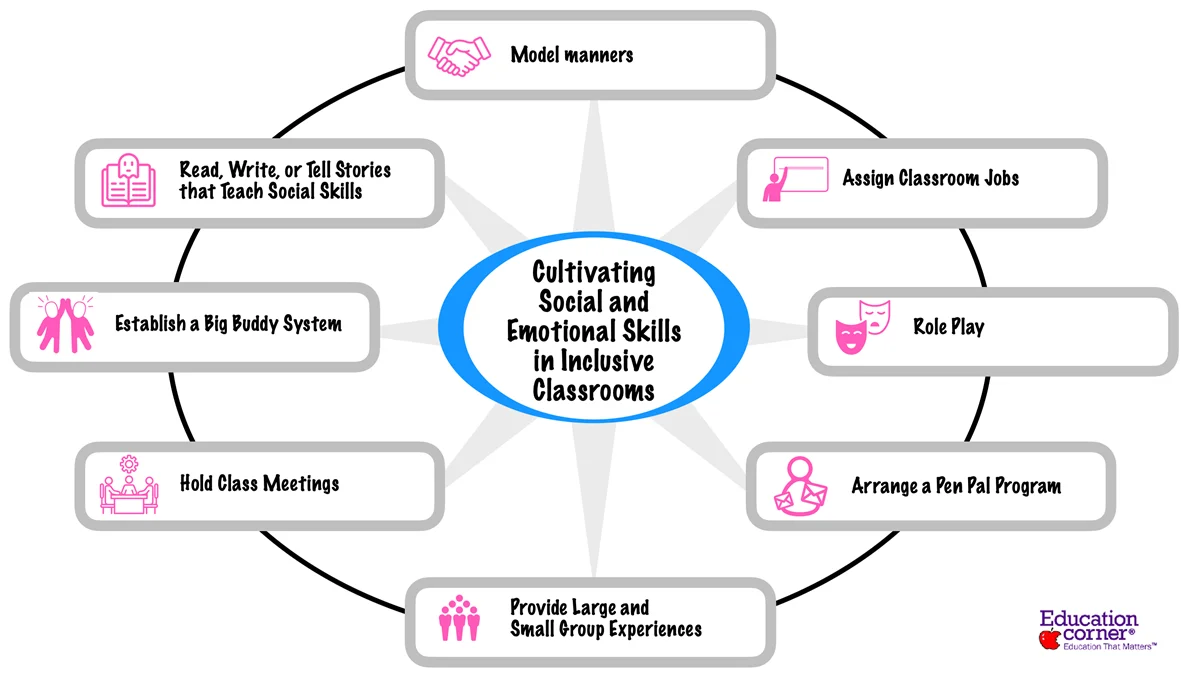

Inclusive educators can teach and reinforce social-emotional development by providing instruction on social skills that meet the needs of a broad range of students in the classroom. Consider using the following eight ideas to cultivate social and emotional skills in your inclusive classroom:

- Model Manners: by modeling inclusive behavior and language in the classroom, teachers can lead by example. A teacher’s welcoming attitude sets the tone of behavior among the students who learn how to socialize and respect one another.

- Assign classroom jobs: classroom jobs allow students to demonstrate responsibility, teamwork, and leadership. Tasks such as handing out papers, taking attendance, and being a line leader highlight strengths and build confidence. Rotate jobs to ensure every student has an opportunity.

- Role-play: throughrole plays, teachers can provide structured scenarios in which the students can act out various social situations, followed by immediate feedback. This is very effective in teaching social skills.

- Arrange a pen pal program: having students in one class write letters to students in another teaches them how to demonstrate proactive social skills through written communication. This is particularly valuable for introverted personalities, who need time to collect their thoughts. Be sure to provide guidelines on language usage, topics, and how much personal information to share.

- Provide large and small-group experiences: these allow students to develop teamwork skills, goal-setting, and responsibility. They help quieter students connect with others while appealing to extroverts and reinforcing respectful behavior. Groups can be self-determined or, at times, prearranged.

Assign roles within the group, such as reporter, timekeeper, etc. Large-group activities could include discussions, projects, and games, while small-group activities can be used for more detailed assignments. Before beginning a group activity, it is a good idea to review group behavior and expectations. - Hold class meetings: class meetings are a wonderful way to teach students how to be diplomatic, show leadership, solve problems, and take responsibility. Hold them weekly to discuss current classroom events and issues. Center the discussions around classroom concerns and not individual problems. Provide guidelines for behavior, prompts, and sentence frames to facilitate meaningful conversation.

- Establish a big buddy system: students must know how to communicate with younger or older peers. In a big buddy situation, an older class pairs up with a younger class for an art project, reading time, or games.

This must be preplanned and carefully designed with students’ strengths and interests in mind. Teachers must meet beforehand to decide on pairings and prepare structured activities. They must also set guidelines for interaction and ideas for conversation. - Read, write, or tell stories that teach social skills: stories teach kids social skills in direct and indirect ways. Those written expressly for this purpose are known as social stories. Find ways to incorporate these into class programs. Set aside time each day to read aloud a story or use them during instructional time.

Adopt a Positive Classroom Management Style

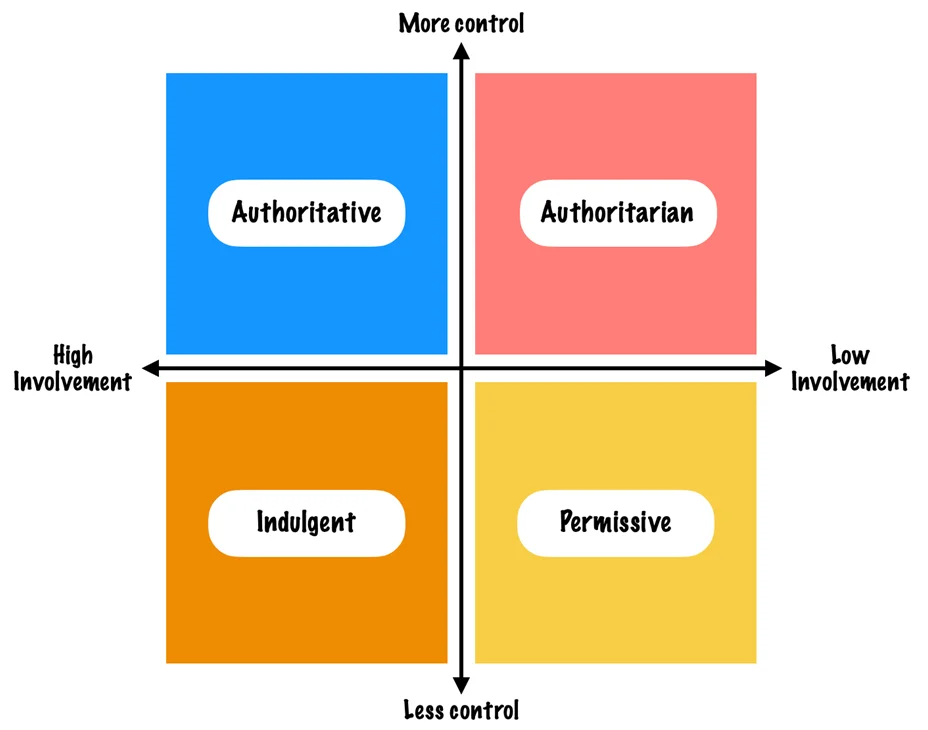

Teachers must use various skills and techniques to keep students organized, orderly, focused, attentive, on task, and academically productive in the classroom. Broadly, classroom management is a function of two parameters: degree of teacher control and level of teacher-student involvement.

Control can range from high, in which teachers explicitly “lay down the law” and strictly enforce it, to low, in which students have no rules or expectations. Likewise, Involvement can range from high to low.

Based on this, classroom management styles can be broadly classified into four categories:

- The authoritarian style is about “I’m the teacher, and we’ll do things my way.” While this style is good for building a well-structured classroom, it does little to increase achievement motivation or encourage the setting of personal goals. Students are likely to be reluctant to initiate activities as they may feel powerless.

- The authoritative style reflects a “let’s work together” attitude. Though limits are placed on student behavior, rules are explained, and students are also allowed to be independent within limits. An authoritative teacher encourages self-reliant and socially competent behavior. He or she encourages students to be motivated and achieve more, often guiding students through a project rather than leading them.

- In an indulgent style, the teacher places few demands or controls on students, accepts their impulses and actions, and is less likely to monitor behavior. The teacher may strive not to hurt the students’ feelings and have difficulty saying no or enforcing rules. While the teacher may be popular, the students lack social competence and self-control. With few demands placed, their motivation drops.

- The permissive style is characterized by a “do whatever you want” attitude. The teacher is uninvolved, places few demands, if any, on students, and appears generally uninterested. The indifferent teacher doesn’t want to impose anything and feels that class preparation is not worthwhile. The teacher promotes an aloof environment where students have little opportunity to observe or practice skills.

Given the intensity of student needs and the pace of activity in inclusive classrooms, routines and expectations must be aligned with the principles of inclusion. A classroom management style that promotes community building, friendships, collaboration, parent participation, and positive behavior management must be adopted. Therefore, inclusive teachers must avoid punitive and exclusionary classroom management.

The authoritative style is often best suited as it encourages independence, is warm and nurturing, and allows control to occur along with explanations. Adolescents are permitted to express their views.

For best results, use an authoritative style while establishing clear expectations for student behavior, developing and implementing routines for students to move and learn safely in the classroom, keeping tasks clear and manageable, and using meaningful, respectful, and positive language when interacting with students.

Reflect and Respond to Student Needs

Reflection is deliberate thinking about our choices as educators and how they affect students’ education. Get to know your students, have one-on-one conversations, use interest surveys, observe them during different activities, and review their files and previous assessments to tailor your approach to individual needs.

When a student requires extra support, look to techniques such as:

- A change in the physical environment.

- One-to-one instruction.

- Positive behavior support.

- Executive function skill acquisition, which addresses the skills that allow people to get things done.

- Development of peer relationships.

An inclusive teacher must reflect on and respond to students’ needs to keep them learning, interacting, and socializing in the general education classroom and avoid exclusion or expulsion.

Designing Inclusive Instruction

Inclusion also extends into the curriculum, comprising the lessons, activities, and student experiences in the classroom. Because inclusive classrooms are not homogenous in ability, religion, culture, or language, teachers cannot use a one-size-fits-all approach.

An inclusive curriculum is one that allows for a diversity of content, material, ideas, and assessment methods. It involves purposefully integrating perspectives that expand and enhance the whole course. It provides students opportunities to engage with a variety of viewpoints and equips them for a global and diverse environment.

All students benefit from responsive and inclusive instructional strategies. For example, a student learning to speak English could benefit from additional support from pictures and illustrations designed for visual learners.

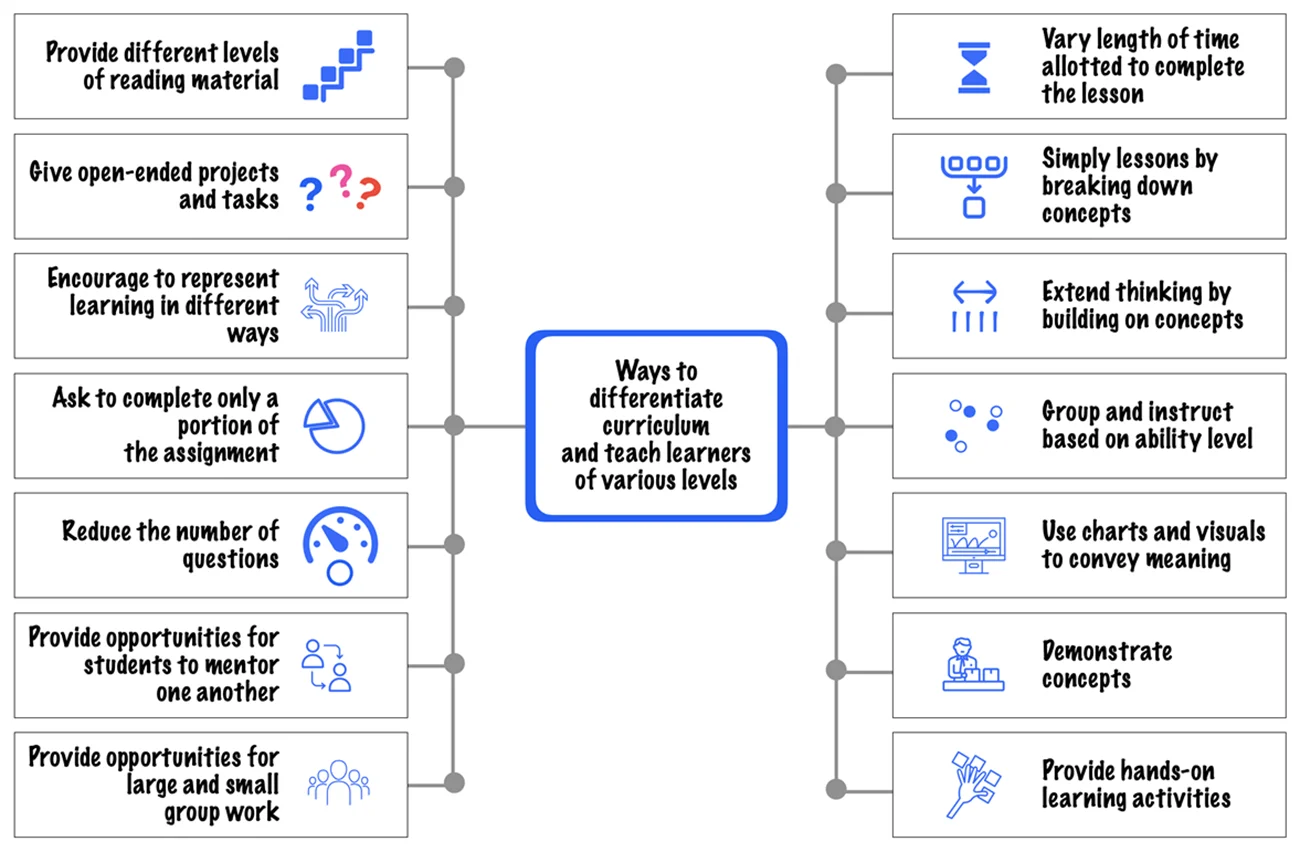

Below are some ways to differentiate curriculum and teach learners of various levels:

Universal Design For Learning (UDL)

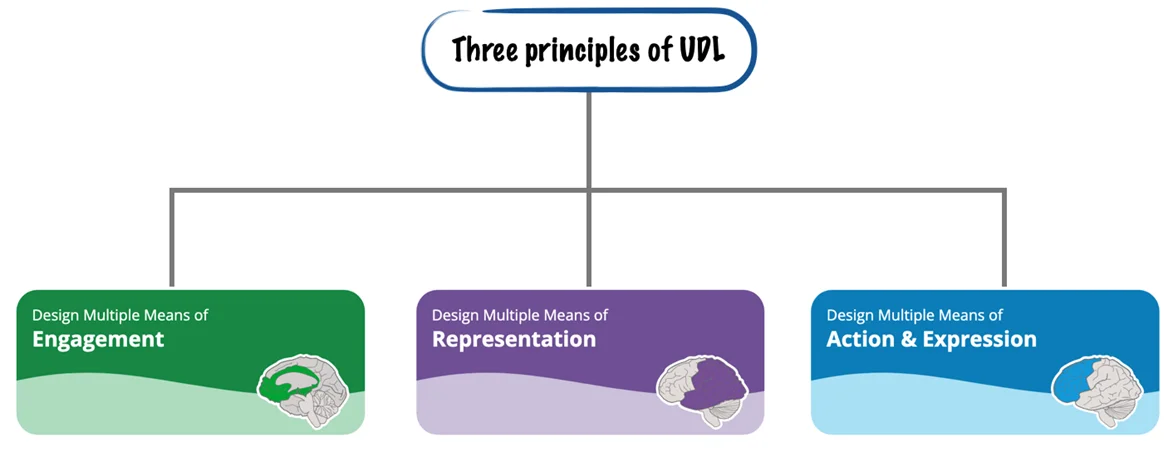

UDL offers a teaching and learning framework that guides the design of accessible and challenging learning environments. It was first developed at CAST (Center for Applied Special Technology), a not-for-profit research and development organization.

The origins of UDL are rooted in classical developmental psychology, neurology (Piaget, Vygotsky), and contemporary cognitive and affective neuroscience. The framework is based on the foundation of the three main divisions of the brain:

- The Affective Network—Responsible for emotional functioning.

- The Recognition Network—Responsible for perceptual and pattern recognition functioning.

- The Strategic Network—Responsible for motor and executive functioning.

These three brain networks provide the foundation for the three principles of UDL:

With UDL, teachers provide lessons and activities such as cooperative learning, differentiated instruction, and performance-based assessment. More specifically, they create lessons and activities that incorporate the following:

- Multiple means of engagement–Teachers provide different ways for students to engage and remain motivated during the lesson, such as inquiry-based projects, self-assessment, and learning software.

- Multiple means of representation–Teachers present information and content in various ways, such as through visual, audio, and tactile materials.

- Multiple means of action and expression–students can demonstrate their understanding of the material in numerous ways, such as written, spoken, artistic, or digital presentation.

UDL can benefit all learners of all abilities and grades, including those working above or below grade level. It prompts teachers to plan ahead with their students’ skills and needs in mind. More information on UDL can be found on the CAST’s UDL Guidelines page.

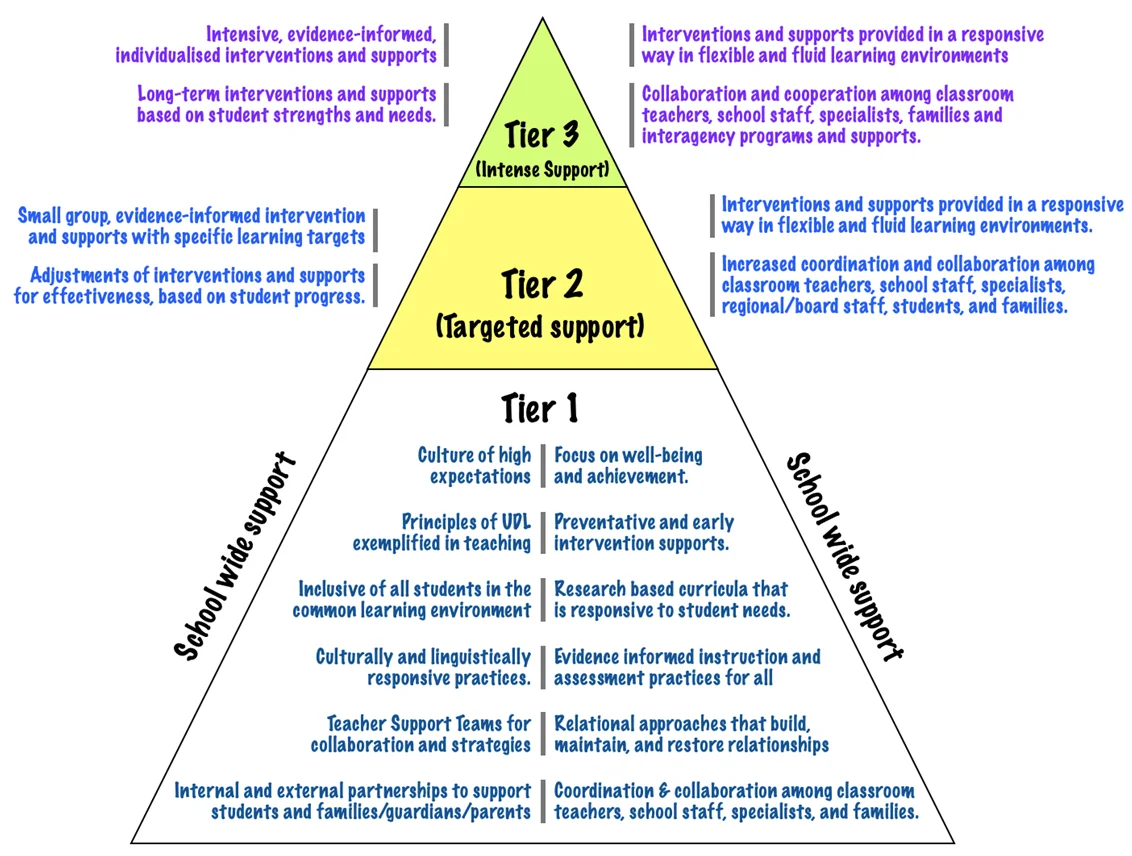

Multi-Tiered Systems Of Support (MTSS)

MTSS is a framework for organizing and providing a tiered instructional continuum to support all students’ learning. Typically, MTSS includes a three-tier triangular model of support:

This hierarchy of tiers ranges from low levels of support to higher, more intense levels. A common term used to describe the transition of services among the three tiers is response to intervention (RTI). A student can move in and out of levels or tiers depending on his or her needs at the time.

MTSS begins with the premise that most students will make academic and behavioral gains by receiving standards-based instruction using highly effective teaching methods like UDL, facilitated by techniques such as scaffolding, explicit instruction, differentiated activities, cooperative learning, and assistive technology.

All school students receive support through regular monitoring of academic and behavioral performance. If a child struggles to meet or maintain the expected academic and behavioral standards, targeted support is provided based on specific needs.

This typically involves small-group instruction within the class or a resource room. If the child still does not meet expectations, he or she will be given intense, frequent instruction in a small-group or one-to-one format.

Accommodations For Learning

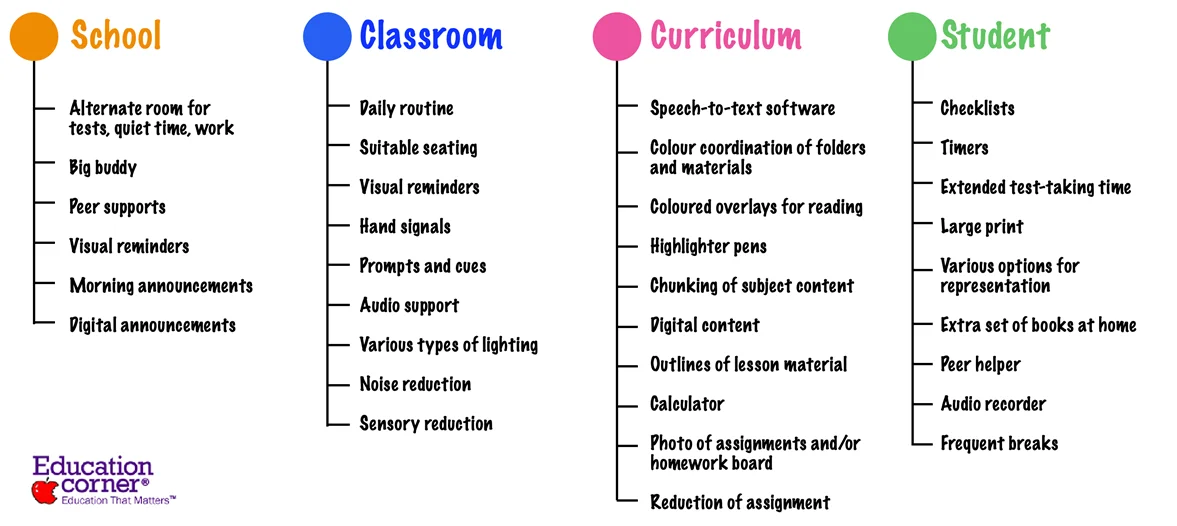

Some students who work at or below grade level may require extra learning support through accommodations. Accommodations are pathways to the curriculum and do not alter the objectives of a lesson or change the difficulty level.

They are designed to alleviate the impact of physical, social, emotional, or neurological issues that might prevent a student from accessing the curriculum.

Dozens of accommodations can be made (some examples are shown above) to address a range of learning needs at various levels, such as the school, classroom, curriculum, and individual levels.

To Sum It Up

Inclusion cannot be realized unless teachers become empowered agents of change with values, knowledge, and attitudes that permit every student to succeed. As education systems continue to move away from identifying problems with learners to identifying barriers to learning, teachers must recognize the experiences and abilities of every student, embrace the idea that each student’s learning capacity is open-ended, and be open to diversity.