It’s easy for teachers to become overwhelmed by all the things that are “wrong” with a student—from a low working memory to poor comprehension to difficulty focusing.

As educators, we often focus on a student’s weaknesses and what the child needs to ‘improve’ on, but too little on their ‘strengths’ and ‘talents.’

This is mainly because our education systems have evolved from a deficit-remediation model in which programs and services are dedicated to “fixing” the deficits by first diagnosing a child’s problems, concerns, ignorance, and defects. While this model has its merits, it fails to provide sufficient information about strengths and strategies to support a child’s learning and development.

In most cases, classes, workshops, programs, and services focus on areas where children are underprepared or weak. Considering deficits and what students need to improve is important; however, when deficits become the focus, students become defensive and feel excluded. Once a child gets a negative label, it often limits the potential options for both the teacher and the child.

Because the purpose of education is to allow every child to fully realize their potential, the strengths-based approach takes a different route. It emphasizes identifying and developing the student’s natural talents, strengths, capabilities, and resources.

It encourages educators to (1) understand that children’s learning is dynamic, complex, and holistic, (2) understand that children demonstrate learning in different ways, and (3) start with what’s present—not what’s absent—and write about what works for the child.

Assessments, teaching, and experiential learning activities are designed such that they enable students to recognize and harness their greatest strengths. This enhances learning, intellectual growth, and academic achievement, ultimately guiding them toward personal excellence.

Teachers create conditions to consciously use strengths in the learning process by focusing on strengths. They begin to see and approach students as a “whole” rather than as an unknown other who ‘lacks something.’

Instead of putting teachers in the roles of fixers, the strengths-based approach puts teachers in the role of facilitators, where they work with the child (and their family) to discover unique resources within the child that can power development. Rather than ignoring the strengths, they utilize them as allies in the child’s quest for development.

What Is a Strength?

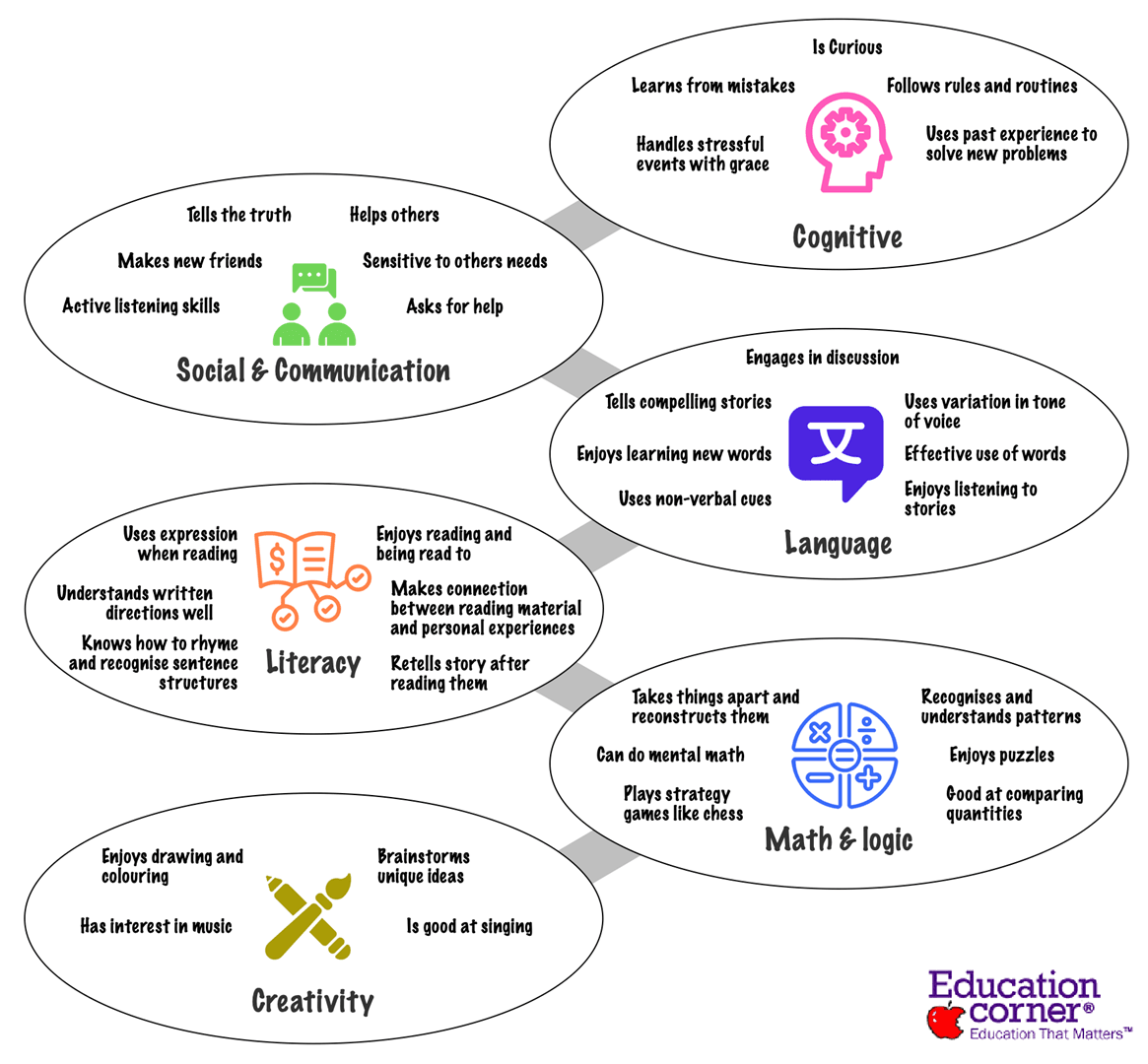

Strengths include skills, abilities, interests, characteristics, and talents. While scientific literature differentiates these terms, in the context of strengths-based learning, they all mean the same.

The following illustration provides cues to identify a child’s strengths in various areas:

A child’s strength can be a particular talent, such as the ability to compute numbers, draw in perspective, or play a musical instrument. It could also be one or more of the six broad positive personality traits that the child exhibits in abundance (courage, humanity, wisdom, sense of justice, ability for temperance/self-control, and capacity to find meaning in something beyond ourselves).

Strength can also include character traits that shape performance. Einstein’s curiosity, Mother Teresa’s compassion, and Neil Armstrong’s bravery are examples of character traits that shaped their personalities.

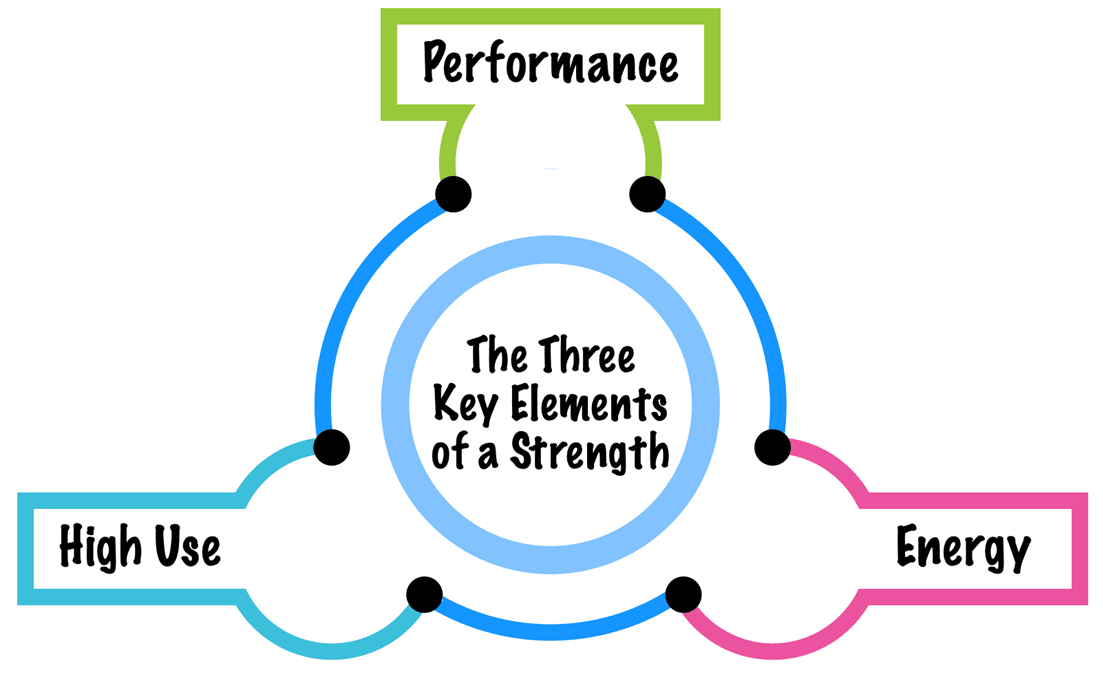

Three elements come together to form a strength, as shown:

To spot a child’s unique strengths, teachers must observe day-to-day behavior and language and ask the following questions:

- Do I see performance? Does the child show above-age levels of achievement, rapid learning, and a repeated pattern of success? For example, a grade-schooler who reads a lot may use more complex words and sentence structures than her peers. A teenager may consistently display a sophisticated understanding of emotions.

- Do I see Energy? Strengths are self-reinforcing. The more they are used, the more the child gets from them. For example, a child with a talent for art rarely tires when drawing or painting.

- Do I see High-Use? Look for what the child chooses to do in their spare time. How often do they engage in a particular activity? How often do they speak about it?

Teachers can use these three elements to avoid pushing children into an area that seems like a strength because they are good at it. It also helps differentiate between whether a child is bingeing on an activity in an escapist way or expressing a genuine strength.

What a Strengths-Based Approach Isn’t

A strengths-based approach is not about describing a child’s learning and development in a positive light while neglecting areas that require development and/or areas of concern. It is also not about framing the learning and development message one way for families and another way for prep teachers.

The approach requires that information is shared consistently. The following table clarifies this in more detail:

| What it A Strengths-based Approach | What it is not |

|---|---|

| Valuing everyone equally and focusing on what the child can do rather than what they cannot do. | Only about ‘positive’ things. |

| Describing learning and development (L&D) respectfully and honestly. | A way of avoiding the truth. |

| Building on a child’s abilities within their zones of proximal and potential development. | Accommodating bad behavior. |

| Acknowledging a child experiences difficulties and challenges that need attention and support. | Fixated on problems. |

| Identifying what is taking place when L&D is going well, so that it may be reproduced, further developed, and pedagogy strengthened. | Minimizing concerns, taking a one-sided approach or a tool to label individuals. |

Principles of Strengths-based Learning

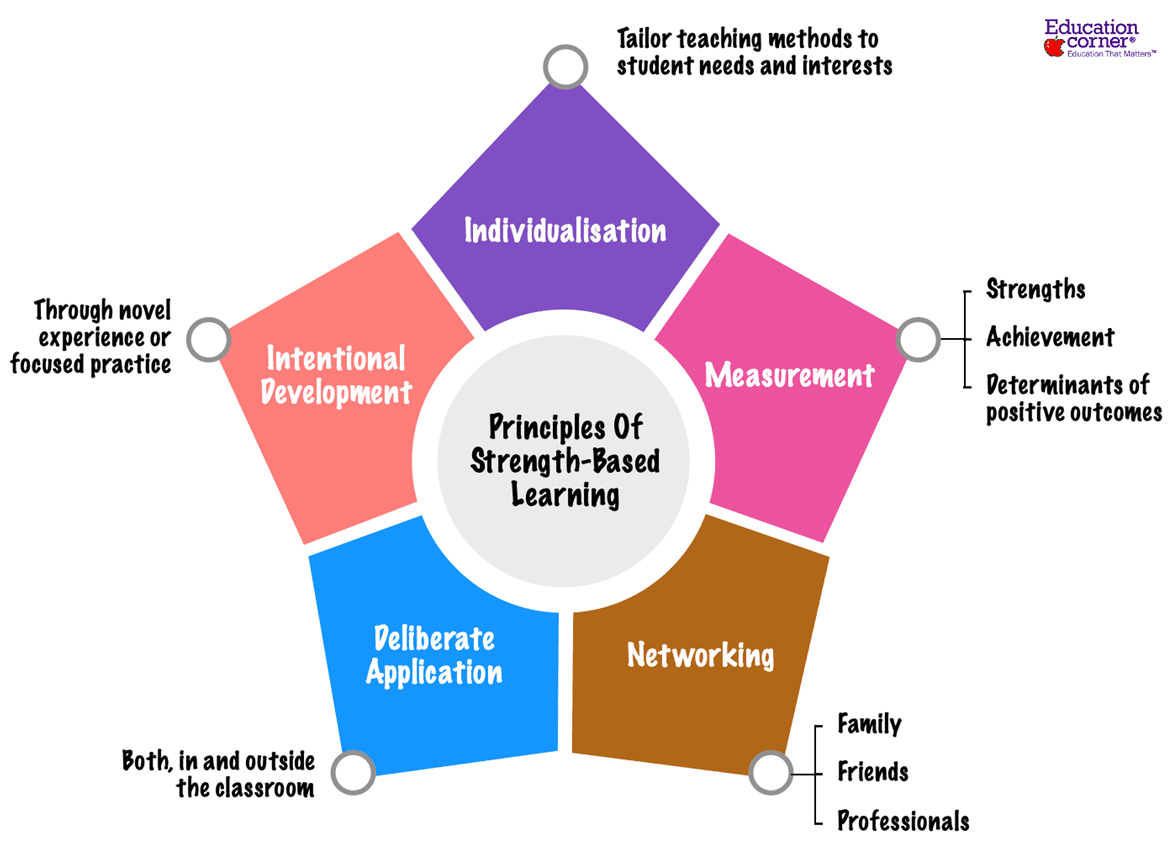

A strengths-based educational approach is best understood as a philosophical stance and daily practice that shapes how an individual engages in the teaching and learning process. Its underlying principles are derived from research in several fields, including education, psychology, social work, organizational theory, and behavior.

Broadly, the concept of strengths-based learning rests on five principles:

Principle 1: Measurement

Educators rely on good data, typically achievement tests and behavioral reports, that shape perceptions of good students and effective schools. The strengths-based approach augments these measurements to include positive traits such as hope, engagement, well-being, and more.

While educational institutions have valued achievement and its associated behaviors, they have struggled to boost it. Including strengths and other positive variables helps develop a more comprehensive picture of academic success, its determinants, and long-term benefits. Because educators can only improve what they measure, including strengths helps explain unaccounted variance in academic success.

A popular tool for understanding student strengths is the Clifton StrengthsFinder. The tool resulted from research that began five decades ago at Gallup, focusing on the empirical discovery of the components of human strength.

Educational psychologist Don Clifton championed this effort, beginning with a series of projects inspired by the question, “What would happen if we studied what is right with people?”

Clifton and his colleagues systematically reviewed the data generated by interviews with over two million individuals to reveal the anatomy of more than 400 types of talent, creating an initial pool of more than 5,000 items that were candidates for a comprehensive measure of positive human qualities.

Clifton StrengthsFinder is available in more than 30 languages today, and over 700,000 students take the assessment annually. It can also be modified for individuals with disabilities to make it more accessible. With 177 questions, it takes 30-45 minutes to complete and identifies 34 themes of talent grouped into four domains:

- Executing: Strengths in this domain help make things happen and get things done.

- Influencing: These strengths enable individuals to take charge, sell their ideas, and persuade others.

- Relationship Building: Themes here focus on building strong relationships, fostering connections, and enhancing team cohesion.

- Strategic Thinking: Strengths in this domain are about absorbing and analyzing information, making strategic decisions, and envisioning future possibilities.

Having identified their strengths, students can carry these descriptors throughout their college and professional lives and share them with their family and friends. Similarly, educators can do more of what they do best throughout their careers by being mindful of their strengths.

Principle 2: Individualization

Individualization in a strengths-based approach refers to policies, practice methods, and strategies designed to identify and draw upon the strengths of children, families, and communities.

Educators personalize learning experiences based on each student’s strengths, encourage goal-setting based on those strengths, and help students apply their strengths in novel ways as part of their developmental process.

Learning experiences that are tailored to a child’s interests become more engaging and meaningful. Because children may vary in their developmental progressions, it is also essential that the curriculum supports teachers in planning learning experiences that are responsive to individual strengths and needs.

Several key elements guide individualized instruction. They can be categorized into three baskets: Content, Process, and Products.

Content

Individualizing content requires pre-testing students so the teacher can identify the right level of instruction. For example, students who demonstrate an understanding of a concept can skip the instruction step and proceed to apply the concepts to solving a problem.

Another way to individualize or differentiate content is to permit the apt student to accelerate their rate of progress. They can work ahead independently on some projects or cover the content faster than their peers.

Several elements and materials can be used to support individualization of instructional content. These include acts, concepts, generalizations, attitudes, and skills. A common way of personalizing content is to vary how students gain access to it.

Individualized instruction designers have stressed the alignment of tasks with instructional goals and objectives. An objectives-driven menu makes it easier for learners to find the next step when entering at varying levels.

Instructional concepts should be broad-based and not focused on minute details or unlimited facts. Teachers must focus on the concepts, principles, and skills that students should learn. The content of instruction should address the same concepts for all students but be adjusted by the degree of complexity to accommodate the diversity of learners in the classroom.

Process

Process individualization refers to the practice of varying learning activities and strategies to provide appropriate methods for students to explore the concepts. It provides alternative paths for students to manipulate ideas embedded within the concept.

For example, students may use graphic organizers, maps, diagrams, or charts to demonstrate their comprehension of the concepts covered. Varying the complexity of the graphic organizer can very effectively facilitate different levels of cognitive processing for students with different abilities.

Processes also include strategies for flexible grouping. Learners are expected to interact and work together as they develop knowledge of new content. Teachers may conduct whole-class introductory discussions of big content ideas followed by small group or pair work.

Student groups may be coached from within or by the teacher to complete assigned tasks. Based on the content, project, and ongoing evaluations, grouping and regrouping must be dynamic and form the foundation of individualized instruction.

Product

Product individualization is about varying the complexity of the product that students create to demonstrate mastery of the concepts. For example, to demonstrate understanding of the plot of a story, one student may create a skit while another student writes a book report.

Students working below grade level can have reduced performance expectations, while those above grade level may be asked to produce work that requires more complex or advanced thinking. A good product allows students to:

- Apply what they can do.

- Extend their understanding and skill.

- Become involved in critical and creative thinking.

- Reflect on what they have learned.

There are many sources of alternative product ideas available to teachers that can be used to motivate students by offering them the choice.

Principle 3: Networking

Networking with personal supporters of strengths development affirms the best in people and provides praise and recognition for strengths-based successes. Because strengths develop best in response to other human beings, networking helps define who we are and who we can become, positioning our strengths as the qualities that establish connections between people.

Children need an encouraging network of supportive human beings who can advocate for and foster their emotional well-being. Networking around strengths produces increased social support. Research on inclusive school environments where differently abled children can fully and equally participate in education shows demonstrated benefits for all.

Teachers can empower students and strengthen the mentoring relationship by being mindful of their strengths. As students discover their own strengths, they can share new information and work to consider other’s strengths.

For example, when providing feedback, a teacher could begin by highlighting what was done well and why (i.e., which strengths were showcased) rather than what was done poorly and why (i.e., which weaknesses undermined performance).

In building networks, other’s strengths can be leveraged to manage personal weaknesses. For example, a larger group of children can bring their best talents together while filling the gaps. Educators must use strengths to help others achieve excellence and move beyond an individual focus to a more relational perspective.

Principle 4: Deliberate Application

Applying strengths deliberately within and outside the classroom helps develop and integrate new behaviors associated with positive outcomes among students. It also shapes educators’ behaviors and the very nature of education in several notable ways.

Educators must select pedagogical approaches that bring out the best in the educational process and seek to model how they leverage personal strengths in teaching, advising, and other domains of life. They must regularly discuss strengths application with students, provide examples or illustrations, and describe experiences that were critical in their own process of strengths development.

A part of the educator’s core responsibility is to draw out the strengths within students by heightening their awareness of such strengths and cultivating an orientation around how students can catalyze those strengths as they approach their education.

This requires educators to devote effort to helping students notice and identify occasions when their strengths are evident in the classroom or when they use personal strengths to complete high-quality assignments.

They must also foster a learning environment where affirming peer-to-peer feedback is a regular feature, and students are taught to cultivate the skill of noting their classmates’ strengths in action. One way to support this is by providing opportunities for students to choose assignment types that allow them to leverage their strengths and provide practice in selecting activities that will bring out their best.

According to self-determination theory, three psychological needs must be met for individuals to function optimally: competence, autonomy, and relatedness.

Helping students understand the connection between their strengths and their personal goals and offering guidance on effectively applying those strengths elicits a feeling of competence.

Providing them with choices and opportunities for self-direction supports their need for autonomy. When educators establish a learning culture in which students view themselves and others through “strengths-colored glasses,” they foster an appreciation for difference, highlight the value of collaboration and teamwork, and establish a powerful sense of relatedness.

Principle 5: Intentional Development

Educators and students must actively seek out novel experiences and previously unexplored venues for focused practice of their strengths. This includes strategic course selection, use of campus resources, involvement in extracurricular activities, internships, mentoring relationships, or other targeted growth opportunities.

The principle of intentional development builds upon others by suggesting that if students are to maximize their strengths, they must cultivate discipline in proactively seeking new experiences that will expose them to information, resources, or opportunities to heighten their skills and knowledge about mobilizing their strengths most effectively.

Research suggests that students’ implicit beliefs about the degree to which their abilities are malleable affect behavior within educational environments. Those with a fixed mindset believe personal attributes are constant, trait-like qualities not amenable to change efforts. They also believe that hard work reveals a lack of innate ability and are likely to avoid tasks that require prolonged effort.

In contrast, students with a growth mindset believe that personal abilities are responsive to developmental efforts. They often view exerting effort as a prerequisite for developing abilities and, therefore, as something to be embraced.

While interventions can influence mindset, merely highlighting positive traits is not enough. If students are not taught to be mindful of the importance of effort, their future performance can be undermined, leading to a fixed mindset and a decline in motivation.

Four Stages of Strengths-Based Approach

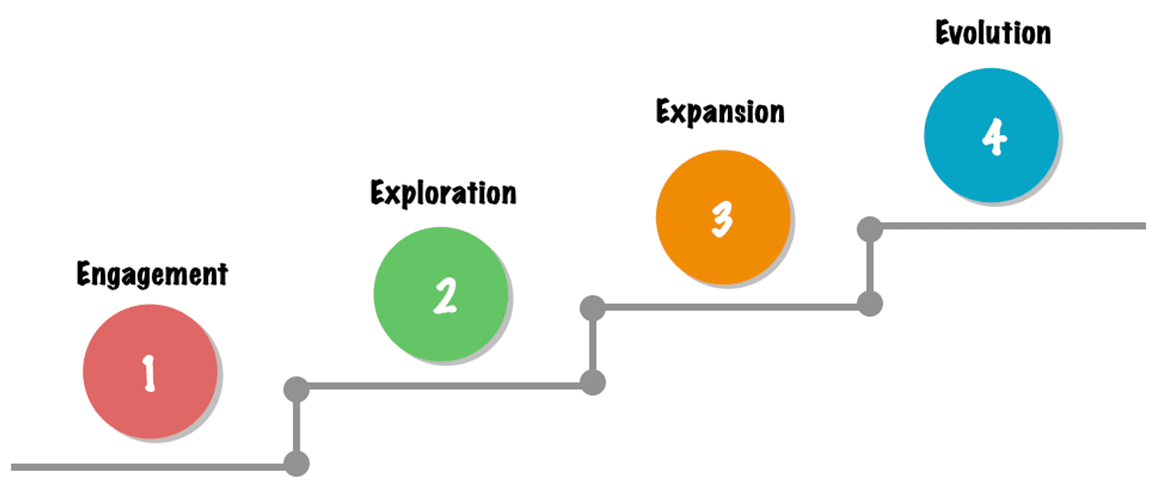

The strength-based approach in the classroom can be divided into four stages:

Engagement

Engagement is the process of setting the tone of subsequent relationships, which usually last throughout the school year and often beyond into subsequent years. In this stage, the teacher works on creating a positively oriented relationship with students, caregivers, and other significant people in the students’ lives.

The emphasis is on discovering and discussing the students’ strengths and establishing positive expectations centered on a child’s positive attributes rather than on any perceived or residual deficits previously encountered in relation to the school.

Positive and effective engagement enables the classroom to be regarded as an affirming social context and the school itself to be viewed positively, which is more likely to be reinforced at home when caregivers feel their children are recognized and appreciated.

Positive engagement is also more likely to foster parental involvement with the school, which has been associated with academic benefits for children, especially children from economically disadvantaged families.

Exploration

Once the strengths intervention has been established throughout the school, students receive a strengths assessment, which provides a springboard of strengths from which to launch a year-long relationship with them.

The exploration stage is a formal and comprehensive assessment of a student’s strengths. It can involve multiple people in the student’s life and span multiple contexts, such as school, home, and recreation.

A simple and comprehensive method of assessing strengths is administering a questionnaire that uses multiple sources of information and assesses various contexts and developmental aspects of students.

The Strengths Assessment Inventory is one such questionnaire explicitly developed to assess a broad spectrum of students’ strengths. It assesses strengths from five naturally occurring domains of functioning and five personal developmental domains. If a strengths assessment questionnaire is not available, other viable alternatives include discussions about strengths with students, caregivers, other educators, and staff members.

Expansion

Once strengths have been identified, students must understand how their strengths can help them achieve goals and overcome challenges. This requires reflection from both the students and those around them.

Schools can foster a culture of strength by involving teachers, peers, staff, caregivers, and the broader community. This approach shifts the student’s identity from negative labels to one focused on positive qualities and capabilities.

In classrooms, limited one-on-one time can be supplemented by integrating strengths into group activities, such as analyzing characters in stories, discussing how strengths are applied, and recognizing peers’ strengths.

For example, students can list the strengths of characters, and classmates can highlight unique traits like kindness, leadership, or a photographic memory. This cultivates the habit of appreciation for diverse strengths and prepares students to apply their strengths in real-life challenges and goals.

Evolution

The evolution stage of strengths-based interventions is about driving active change by challenging students to use their strengths in academic, behavioral, emotional, and social contexts.

Educators help students see their potential by building positive relationships and highlighting how others value them. For example, simple activities such as building a “strengths wall” where strengths kids exhibit are posted on a wall provide tangible reminders of students’ abilities, aiding discussions on goals, challenges, and solutions.

Educators can address frustrations, resolve conflicts, and encourage collaboration by reminding students of their strengths. This approach enables personalized problem-solving and helps students regain confidence. It also fosters mutual respect, leading to productive dialogues between educators and students about applying strengths to overcome difficulties.

How to Practice a Strengths-Based Approach

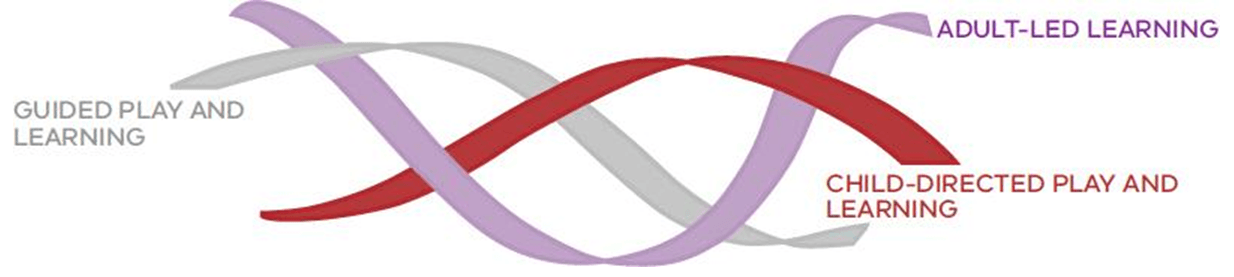

Use Play To Integrate Teaching And Learning

Learning is an active process that must involve children’s engagement. Play can stimulate and integrate a wide range of intellectual, physical, social, and creative abilities in children. Active engagement and attunement to children in their play can extend and support learning.

Integrated teaching and learning approaches combine guided, adult-led, and child-directed play and learning. When educators are actively engaged and responsive to children, immediate learning and ongoing assessment opportunities can occur, leading to meaningful and comprehensive discoveries of the child’s strengths.

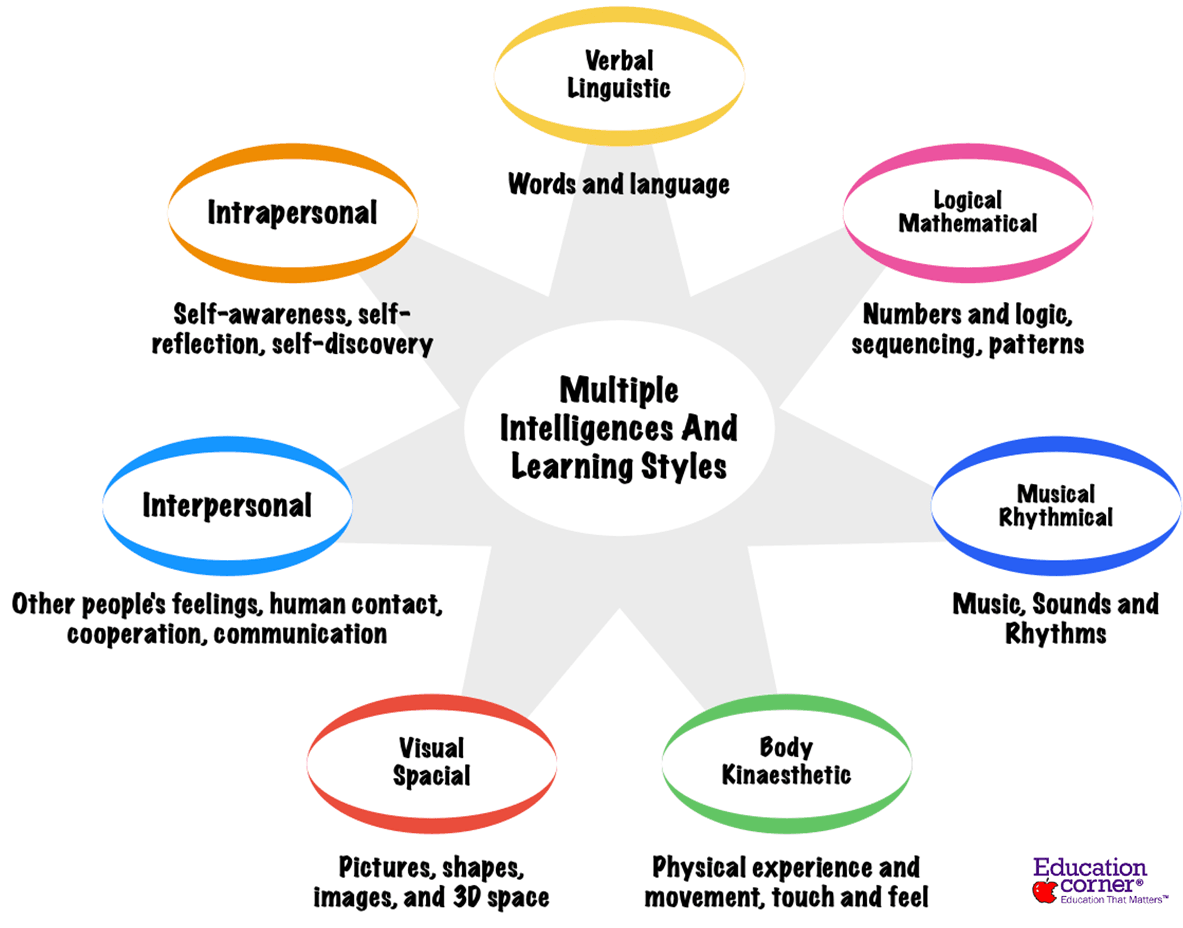

Be Mindful Of Multiple Intelligences And Learning Styles

Children have varying intelligence and learning styles, which they use to process information and express meaning. They use one or more of these styles to understand and learn new concepts and demonstrate their learning through making, sharing, and negotiating meaning.

Understanding learning styles helps educators recognize how children learn or solve problems. How much children learn depends on whether the educational experience is geared toward their particular learning style—in other words, whether it responds to their preferred learning style.

Use Reflective Practice

Reflective practice is best described as a continuous process that involves educators thinking about their own values and professional practice and how their values and practice impact each child’s learning and development.

It allows educators to develop a critical understanding of their own practice and continually develop the necessary skills, knowledge, and approaches to achieve the best outcomes for children. It also helps educators create opportunities for children to express their thoughts and feelings and actively influence what happens in their lives.

Be Mindful Of Equity And Diversity

A child’s personal, family, and cultural histories shape their learning and development. Children learn best when educators respect their diversity and provide the best support, opportunities, and experiences.

To that end, educators must:

- Ensure every child and their family’s interests, abilities, and culture are understood, valued, and respected.

- Maximize opportunities for every child.

- Identify areas where focused support or intervention is required to improve each child’s learning and development.

- Recognize bi- and multilingualism as an asset and support children in maintaining their first language.

- Promote cultural awareness in all children.

Inclusion is strongly linked to the strength-based approach. Promoting development and belonging for all children by creating high expectations for every child and building on the strength of families and backgrounds ensures access, engagement, and meaningful participation of all children in their learning and development.

Assess Learning And Development

Assessments aim to understand what children have learned, what they are ready to learn, and how they can be supported. Assessment must occur continually in different contexts and ways to best reflect a child’s progress and provide a holistic view.

Through assessment processes, the educator and the family must understand what children are ready to learn and how they can support them. Assessments must also be ongoing and include various methods that capture and validate different pathways children take toward achieving outcomes.

They must not focus exclusively on the endpoints of children’s learning but give equal consideration to the ‘distance traveled’ by individual children. They must not only recognize and celebrate the giant leaps but also the small steps children take in their learning.

Writing Strength-Based Statements

A strength-based statement must tell the reader what learning and development has taken place and what strategies have been used to support the child’s learning and development.

The following are some factors to consider when writing strengths-based statements for a child:

Relationships And Communication

When good relationships and communication exist, families better understand the statement’s content and will support what is written. Relationships and communication also help families celebrate their children’s achievements.

Quality relationships and consistent, authentic communication can make a difference. It is essential to engage families in conversations throughout the year, particularly before the statement is written. If needed, organize an interpreter to help support the family.

Ethical Practice, Honesty, And Transparency

It is critical to be honest and transparent when writing statements. Educators must feel confident discussing what is written in the statement with a child’s family and ensuring they fully understand the content before giving consent to share it with the school.

A strength statement should never come as a surprise. It should represent the professional judgment of the child’s abilities—what they can do, create, write, draw, and express—and the strategies that effectively support their success.

Clear, Specific And Concise

Statements should be written in clear, specific, and concise language that is easily understood by all stakeholders. They should highlight a child’s knowledge, interests, achievements, and challenges, respect the family’s background and cultural needs, and provide guidance on effective strategies to support their learning and development.

Suggested Inclusions For Statements

The table below provides some suggested inclusions that can strengthen the information in strength statements and provide the reader with valuable insight into a child’s learning and development:

| Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Triggers | Outline what event, situation or circumstance helps or hinders a child’s learning and development. | 1:1 adult support in whole group contexts, Paired or small group work. |

| Qualifiers and/or examples | Provide detail on how often something happens, for how long it happens, whether adult support is required and what support has worked. | Concentrates for up to 10 minutes, Accesses art-based activities approximately 3 times per week. |

| Dispositions for learning | Describe the child’s tendencies to respond in characteristic ways to learning. | Willing to persevere, Confident with new experiences. |

| Multiple intelligences and learning styles | Explain how the child constructs their understanding of the world and how they convey that understanding to others—in other words, how the child makes and expresses meaning and understanding. | Through music and rhythm, Hands-on exploration. |

| Strategies | Show what plan, activity or learning sequence has been developed and used in order to enhance a child’s learning and development, based on a child’s learning dispositions and what they know in any given context. | Visual supports, Verbal and tangible reinforcements. |

In summary, a strengths-based approach shifts the focus from “fixing” deficits to nurturing and amplifying a child’s unique talents and abilities.

Through individualization, networking, and deliberate application, educators create a more engaging and supportive learning environment where every child feels valued and empowered to reach their full potential.